POLITICS

Myanmar’s census controversy

GWEN ROBINSON, senior Asia editor, Nikkei Asian Review

March 13, 2014 00:00 JST

BANGKOK — Myanmar will shortly launch the most comprehensive survey of its population since the country’s last full census under British colonial rule in 1931. Over 12 days from March 30, more than 100,000 designated “enumerators,” mainly younger school teachers, are set to visit an estimated 10 million or more households across the country with an exhaustive list of 41 questions in efforts to gather data on an estimated population of 60 million.

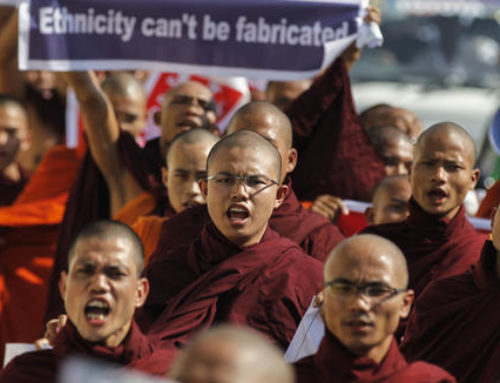

In an escalating controversy targeting the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and foreign donor governments, which are funding the costly exercise, critics have warned that the census in its planned form could do more harm than good in a country of numerous ethnic and religious groups, with a Burman Buddhist majority estimated at 60% to 70%.

Unlike a flawed 1983 survey conducted by the then-military regime, which put just seven questions to 80% of the population and another 11 to a random sample of 20%, the forthcoming census will cover topics ranging from sanitation and child health to ethnic origin and religion.

Too much?

In announcing the census plan, the UNFPA in February hailed the exercise as “both timely and historic,” noting that “complete, accurate and reliable” census data could help steer Myanmar’s socioeconomic development and other reforms. In early March, President Thein Sein promised the survey would “show respect for human rights” and help display Myanmar’s “unity.”

But critics such as the Brussels-based International Crisis Group (ICG) and the Netherlands-based Transnational Institute (TNI), as well as local civic leaders, warn that the questions and timing of the 2014 Population and Housing Census could trigger further violence against minority Muslims, undermine the government’s reform process and set back already shaky peace initiatives with armed ethnic groups.

In a highly critical note in February, the ICG said the census as planned was “ill advised” and “fraught with danger,” and could further fuel rising communal tensions.

The main fear is that census data will reveal a far higher proportion of Muslims among the majority Buddhist population than the 4% or so shown in the 1983 survey. In the past 18 months, Buddhist activist groups — led by extremist monks — have launched attacks on Muslim communities, particularly against stateless Muslim Rohingya in Rakhine state in Myanmar’s west.

Another concern is that questions about ethnicity could undermine peace talks with armed ethnic groups just as the government is trying to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire with more than 14 of these groups. Ethnic leaders have complained about the rigidity of categories that designate 135 ethnic groups — set after the 1983 census — and allow little scope for those of mixed ethnic backgrounds.

Too soon?

The biggest issue, however, is timing. There is the risk that census results due in the lead-up to national elections in late 2015 could exacerbate disputes over voter representation.

“Instead of creating the opportunity to improve inter-ethnic understanding and citizenship rights, the census promises to compound old grievances with a new generation of complexities,” said TNI in a joint report with research group Burma Centrum Nederland.

Both TNI and ICG have said the census process should be urgently scaled back to six or so key demographic questions, while postponing questions that ICG said are “needlessly antagonistic and divisive — on ethnicity, religion, citizenship status.”

UNFPA representatives recently ruled out delaying or modifying the census. But, warned TNI-BCN, if it is not scaled back, the census “will transform the social fictions produced by unreliable data into highly problematic ‘social facts’ that set new national parameters on ethnicity” just when peace-building is starting and when new and participatory ways “are needed to deal with the state failures of the past.”

Some also question the sharp rise in the cost of the exercise, which has grown to $74 million from an initially projected budget of $58 million.

Yet, without reliable data, say Myanmar officials, the government cannot properly plan budgets nor calculate economic statistics including per capita gross domestic product.

“Yes, a census is a good thing for national planning and development, if managed with sensitivity,” noted The Nation, a Bangkok-based English-language newspaper. But it warned that “the leaders in Myanmar need to ponder the possible negative consequences of asking questions at this point in time about ethnicity, citizenship, race relations, communal violence and stateless people, like the Rohingya, who the Myanmar authorities insist on calling ‘Bengali’ to try to minimize any link to areas where they live in Rakhine state and areas along the country’s western border.”

To postpone, modify or cancel? Two leading Myanmar experts give diverging views on Myanmar’s census controversy at Nikkei Asian Review online. Dr David Steinberg proposes cutting back the census from 41 questions to five or six “politically and culturally neutral questions.” Dr Robert Taylor meanwhile argues that “hiding from reality” gives opponents of the census a license to invent “all kinds of claims.”

See these commentaries on NAR’s web site,

https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics-Economy/International-Relations

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW