Ugly social media wars fueling intolerance in Asia

Similar tactics are cropping up across different areas and different faiths{1st Photo Caption: A Twitter logo is seen in front of a computer screen displaying an Islamic State flag. Twitter says it has shut down tens of thousands of terrorism-related accounts. © Reuters}

POLITICS

Ugly social media wars fueling intolerance in Asia

Similar tactics are cropping up across different areas and different faiths

SIMON ROUGHNEEN, Asia regional correspondent, and GWEN ROBINSON, Chief editor

December 13, 2017 3:14 pm JST

JAKARTA/YANGON — An ugly new campaign against Muslims in Myanmar began around 2012 via social media, led by Buddhist supremacists and other anti-Muslim groups employing highly targeted attacks. One tactic involved posting photographs and addresses of individual Muslims on Facebook and other online forums, along with messages urging followers to attack them or to boycott their businesses.

A key culprit in this was the ultranationalist Buddhist group formerly known as Ma Ba Tha, and its precursor, the 969 movement, which often used doctored photographs and fake claims to stoke anger against Muslims.

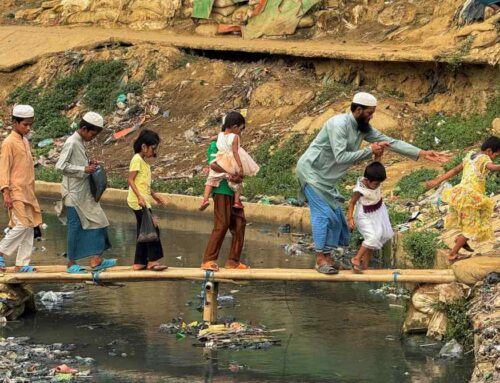

Such provocations fanned the flames of anti-Muslim sentiment in Myanmar for years before tensions exploded in 2016, resulting in more than 800,000 mainly stateless Rohingya Muslims fleeing the country and sparking a humanitarian crisis.

Disturbingly savvy

Similar social media tactics are being used by religious extremists across Southeast Asia. In Indonesia, the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), a Sunni Islamist group, frequently uses Facebook to track, humiliate and organize assaults on critics. In one high-profile case, FPI activists dragged a 15-year-old boy of Chinese descent from his Jakarta home at midnight and beat him for making comments the group considered insulting.

“The FPI members and sympathizers have grown savvy in using digital media to systematically identify and harass those they disagree with,” Kathleen Azali, a researcher at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, wrote in a recent paper.

Platforms such as Twitter have become “weaponized” in Asia in much the same way as they have in the West, according to Indonesian political commentator Wimar Witoelar, who has 439,000 Twitter followers. “So interaction is more often divisive than not. You cannot form a consensus. Instead, you sharpen your differences.”

Social media also offers myriad communications channels for militant and terrorist groups, boosting the flow of money and Southeast Asian recruits to groups such as Islamic State. “There is an increasing trend for terrorist activities, terrorists and terrorist organizations to raise … funding on social media,” Kiagus Ahmad Badaruddin, head of Indonesia’s anti-money laundering agency, said recently.

Recent innovations have expanded the uses of some social media platforms, which were mainly effective for those who could read, noted Robert Templer, director of the Barcelona-based Higher Education Alliance for Refugees. “Widespread illiteracy, for example among the Rohingya population of Myanmar, meant that many avenues for online information and radicalization were closed,” he said.

Now, WhatsApp and other applications that enable people to send voice or video messages have become popular, and are said to have been a key recruitment and organizational tool for leaders of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, the militants behind the October 2016 and August 2017 attacks that triggered the brutal military campaign against the Rohingya exodus, Templer noted.

“Most radicalization is face-to-face — particularly outside of Europe,” he added. “Online radicalization tends to be something in which those who are already radical and even violent seek justification for their views online, but they do not acquire those views on the internet.”

Michael Vatikiotis, Asia director of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, cited recent findings by an Islamic university in central Java showing that efforts to counter online radicalism with a moderate counternarrative were failing. “Social media is a key driver of interreligious tension in the Indonesian context,” he said.

Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Microsoft in June formed The Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism. The companies said last year that they had begun sharing the “hashes,” or unique digital “fingerprints,” of the “most extreme and egregious terrorist images and videos we have removed from our services — content most likely to violate all of our respective companies’ content policies.”

But that move will only slow the dissemination of jihadist content — especially as activity shifts to encrypted smartphone chat applications such as Telegram, which was blocked temporarily in Indonesia this year.

Additional reporting by NAR Asia regional correspondent Marwaan Macan-Markar

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Article:

Religious extremism poses threat to ASEAN’s growth – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Religious extremism poses threat to ASEAN’s growth

Aided by social media, hardliners gain mainstream support