Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism

Myanmar’s de facto leader takes the flak in uneasy military relationship{1st Photo Caption: Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi speaks to the Nikkei Asian Review in Naypyitaw on Sept. 20. (Photo by Shinya Sawai)}

POLITICS

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism

Myanmar’s de facto leader takes the flak in uneasy military relationship

GWEN ROBINSON, Nikkei Asian Review chief editor

September 28, 2017 10:00 am JST

NAYPYITAW It is hard to imagine when meeting Aung San Suu Kyi that within a matter of months, she has gone from what the Dalai Lama once described as “one of the great heroes of our time” to an international hate figure. In a rare interview, she is courteous though aloof, impeccably mannered and exquisitely dressed. She shows occasional signs of strain although she still looks at least a decade younger than her 72 years. Little in her speech and mannerisms betray signs of the agitation or angst that might accompany an outpouring of condemnation.

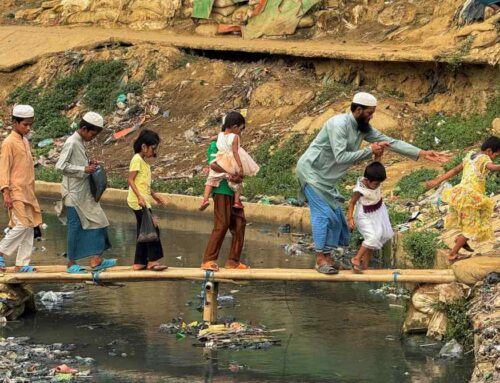

From 1990, international leaders urged her release from house arrest; they received her royally during her visits abroad from 2012; and they hailed her rise to power. Today, she is widely blamed for failing to halt the ferocious military crackdown on Rohingya Muslim communities in western Myanmar and the exodus in waves of half a million refugees into neighboring Bangladesh.

She maintains as she has all along that her government has acted in accordance with the law and that violators — on all sides — will be brought to justice. “Whatever we are doing, we are doing in accordance with the law,” she said.

A Rohingya refugee from Myanmar carries a child in a sack and walks through rice fields after crossing over to the Bangladesh side of the border near Cox’s Bazar on Sept. 1.© AP

When pressed, Suu Kyi shows no signs of regret over her vilification: How does she feel that supporters and friends of just six months ago have become vociferous critics, that entire governments, once supportive, have turned on her?

“Actually, nothing is surprising, because opinions change and world opinions change like any other opinion,” she stated in her precise, English-accented tones. “We have found — and this is quite understandable — countries that have been through a transition process themselves are much more understanding than those which have never gone through such a process.”

Her government has justified the military campaign as a response to attacks by a Muslim militant group calling itself the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army on police and army facilities in Rakhine State. The first attacks, in late 2016, killed nine police and triggered an exodus of nearly 90,000 refugees into neighboring Bangladesh and added tens of thousands to the 120,000 or so internally displaced people from earlier violence in 2012 and 2013. They still live in camps inside Myanmar.

But the latest operation, unleashed after attacks on 30 police and military facilities killed 12 personnel on Aug. 25, was on an unprecedented scale, driving out an estimated 420,000 refugees amid the destruction of more than 210 villages and reported killings, arrests and mob violence by local Buddhist groups. As accusations mounted against Suu Kyi for presiding over “ethnic cleansing policies,” her former supporters turned against her in droves. In a striking illustration of the ugly mood taking hold in Myanmar, the military campaign has gained much public support at home.

As the enormity of the crisis unfolded, she maintained silence, further infuriating her international critics — even as her dwindling circle of defenders warned that she was powerless to direct a military that controlled all security-related matters in the country.

Some, such as former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, have gone as far as to warn that the military is deliberately undermining Suu Kyi to prepare the path for a takeover. By putting her in a position where she must defend the country’s widely loathed Muslim minority, they hoped to weaken her, Rudd recently wrote in The New York Times. Others have argued that she is complicit in, or indifferent toward, the unfolding crisis.

The truth behind Suu Kyi’s attitude, according to insiders, is somewhere in between and lies in a subtle power shift that has seen the military gain momentum since the first appearance of ARSA militants last October — even as Suu Kyi has taken the full brunt of international outrage. Predictably, the military’s commander in chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing has strongly defended the security operations in speeches and via social media, and said recently that Rohingya have “never been an ethnic group in Myanmar.” He told the visiting Japanese vice foreign minister on Sept. 21 that “Bengalis [a term suggesting the Rohingya are interlopers from Bangladesh] have opposed the government’s frequent efforts to solve Bengali affairs in that region in accord with the law.”

Houses burn in the village of Gawdu Zara, northern Rakhine State, on Sept. 7.© AP

Highlighting the West’s dilemma, even diplomats critical of Suu Kyi’s stance admit the dangers of excessive international pressure. If she was to be politically damaged at home and abroad amid global censure, it could strengthen the military’s hand. “She is all there is, the West can criticize but only up to a point,” said one, noting the absence of heirs in Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy.

Suu Kyi spoke to the Nikkei Asian Review just a day after she broke her international silence on the Rakhine issue in a key Sept. 19 speech in Naypyitaw, billed as a diplomatic briefing on government efforts at “national reconciliation and peace.”

Unlike most media interviews with top officials in Myanmar, no questions had to be submitted in advance of our meeting. She appeared exactly on time and fielded every question with unruffled style, whether it was about ethnic cleansing accusations, poverty alleviation or banking regulation.

The day’s headlines in the state-owned Global New Light of Myanmar quoted a line from her speech: “Myanmar does not fear world scrutiny.” Yet like many of her assertions, it was wide open to question, in this case about the government’s steadfast rejection of the United Nations Human Rights Council request to send a fact-finding mission to the country, and its repeated denials of systematic military abuses. “We have not changed our opinion with regard to the fact-finding mission,” she said.

In her days as a political prisoner, Suu Kyi cultivated a close circle of journalists. But she has never liked being questioned by the media — even less so in recent years. Her decision to speak shows the extent to which she felt the need to respond.

Throughout the 50-minute interview, she is quietly confident with no hint of defensiveness. It is this kind of inscrutability and self-assurance that drew admiration every time she defied the generals from the late 1980s and gave stirring speeches at massive rallies, when she endured lonely years of house arrest, and when she faced down military thugs in an ambush that killed scores of her supporters in 2003. And it is the same inscrutability that has driven the world into a rage.

The real question is whether her stiff upper lip approach masks a subterranean power struggle that could diminish her further. The previous day, she rejected claims in an interview with Radio Free Asia that she had “softened her stance” on the military since taking power last year, adding: “We have never criticized the military itself, but only their actions. We may disagree on these types of actions.” In her Nikkei interview she admitted a “change” in the relationship, but would only say: “Of course, a new relationship is starting. Things are changing all the time. I don’t think it’s a bad change.”

Myanmar military commander-in-chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing looks at Aung San Suu Kyi during cross -party talks at the Presidential palace in Naypyitaw in April 2015. © Reuters

MILITARY TENSIONS Despite her discreet and careful path through the minefield of military relations, Suu Kyi gives clues to internal tensions in the interview. Her words seem carefully chosen, which makes it initially puzzling why she left herself open to criticism in her address. She insisted that since Sept. 5, there had been no armed clashes and no “clearance operations” (the military’s term for its brutal sweep of Rohingya communities). In reality, it was only after Sept. 5 that the bulk of 420,000-plus refugees fled to Bangladesh and most of the 210-plus villages destroyed were razed, many by unidentified forces including local mobs.

The numbers speak for themselves. The displaced Buddhists are in the tens of thousands, while among Rohingya communities, more than half a million people have fled since 2016. Her claim that 50% of villages remained intact was also telling. For a speech intended to reassure an international audience, the statement had the reverse effect.

On the supposed halt to military operations, she questioned again in the interview why the majority of refugees had left since Sept. 5, and acknowledged suggestions of paramilitary and mob activities. To some analysts it was a further hint of deep disagreement with the security forces. “I just wondered why people started leaving after things had quieted down. It could be they were afraid there might be reprisals; it could be for other reasons … it’s a possibility [that paramilitary groups mounted fresh attacks] … we’ve got to find out why all the problems started in the first place.”

Beyond what some say is a messianic streak, she feels a strong obligation — not just to “the people,” a factor she evokes constantly — but also to her belief that she must complete her father’s unfinished mission (Aung San, Myanmar’s independence leader, was assassinated in 1947).

What she will never say while in government is that the appropriate target for international scrutiny might be the military commander in chief. Last year, Min Aung Hlaing extended his term to 2020, the year of the next election. Just before Suu Kyi visited Brussels in early May, where she was grilled on her government’s human rights record, he visited Austria and Germany, where he was received by honor guards and discussed possible military hardware deals. Similarly in August, he visited Japan where he was received by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and toured factories.

These days, there is almost no direct contact between Myanmar’s two key leaders, say insiders. One thing is clear, though: neither of them intend to go anywhere before 2020.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

INTERVIEW:

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations

Looking at the Rohingya crisis and beyond, Myanmar’s leader discusses issues facing her government

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her? – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

REPORT ON HER BIG SPEECH

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her?

Myanmar’s state counselor treads cautiously along a precarious line

Myths and realities behind the Rakhine crisis – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

A BACKGROUNDER, “Myth and realities behind the Rakhine crisis”

Condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi highlights ironies of Myanmar’s recent history

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Economic and business implications:

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook

Looming ‘humanitarian catastrophe’ dampens international relations, business sentiment