“Myth and realities behind the Rakhine crisis”

Condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi highlights ironies of Myanmar’s recent history{1st Photo Caption: Myanmar’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, left, talks with Commander-in-Chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces General Min Aung Hlaing at the airport in Naypyitaw on May 6, 2016. © AP}

POLITICS

A BACKGROUNDER,

“Myth and realities behind the Rakhine crisis”

Condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi highlights ironies of Myanmar’s recent history

GWEN ROBINSON, Chief editor

September 12, 2017 2:27 am JST

NAYPYITAW — The international outcry over Myanmar’s escalating Rohingya refugee crisis masks several ironies that have fueled an intensifying propaganda war since the Aug. 25 attacks by Muslim militants on security facilities in Rakhine state. The first is the resounding condemnation of the country’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, while the real commanders behind the brutal “clearance operations” targeting Rohingya communities have stayed out of the political frontline.

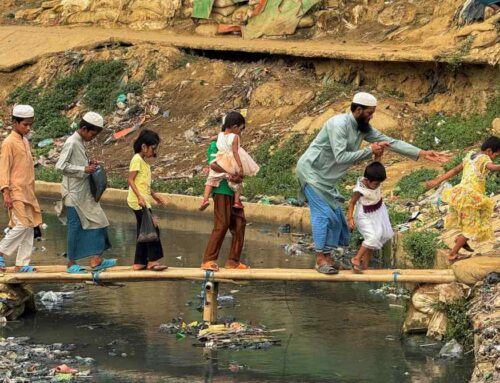

On the international front, Suu Kyi has been widely criticized for her silence and her perceived refusal to halt a military campaign that has driven more than 300,000 refugees — mainly Muslim Rohingya — into neighboring Bangladesh in just over two weeks and razed dozens of villages amid reports of summary executions, detentions, torture and mob violence.

Former supporters, from presidents to nongovernmental organizations, and many of her fellow Nobel laureates seem to have forgotten that in Myanmar’s twisted quasi-democracy, Suu Kyi is barred from the presidency due to constitutional restrictions and has no power over the military. Her title of state counselor, while akin to prime minister in a Western democratic system, stops short when it comes to national security matters.

Even those familiar with the strict limits of her position have been enraged by her silence. Reinforcing her aloof image, several insiders in her National League for Democracy government attribute the lack of response to her fear of upsetting the fragile balance of power, and her belief that she must not appear “weak” in domestic eyes.

Yet, behind the campaign that has shocked the world and triggered one of the biggest mass migrations in recent history is one man with extraordinary powers, the military Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing.

Myanmar’s commander-in-chief, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing inspects officers during a parade to commemorate the 72nd Armed Forces Day in Naypyitaw on March 27. © AP

Despite the country’s steady democratization since 2011, after nearly five decades of harsh, secretive military rule, the armed forces retain total control of security matters in Myanmar, including the three security-related cabinet posts; a 25% allocation of all parliamentary seats; and veto power over changes to the constitution.

Over the past year, the commander-in-chief has honed his international profile — making overseas visits, increasingly to Western countries which once shunned contact with Myanmar’s military. His relatively recent destinations have included Japan, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Italy, India and Thailand, and on some trips, including in Germany, he has been received with military honor guards. In efforts to forge better relations with the still-powerful generals after years of sanctions, key countries including the U.S., Japan, and some European Union countries have been encouraging exchanges and mid- to high-level contacts — and in some cases, showing off military technology and hardware and giving training to Myanmar military and police.

It is Myanmar’s military commanders who unleashed on the Rohingya communities of northern Rakhine a security apparatus known for ruthless tactics in fighting insurgencies and quelling political dissent. The state counselor, according to government insiders, was “barely informed — and even then given the sketchiest of details.”

The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, the militant group behind the Aug. 25 attacks and an earlier series of raids on police posts along the Bangladesh border, has engaged in some skirmishes, although casualties among the Rakhine Buddhist community and among the security forces remain low, with deaths in the low dozens compared with nearly 400 deaths of ARSA fighters in the week after the attacks, and a total 1,100 to 1,300-plus Rohingya deaths as of Sept. 9, according to estimates by media and some Yangon-based diplomats.

ARSA’s relatively small numbers — the military claims 6,000 fighters while independent local and international researchers suggest they number from 1,500 to 3,000 — and crude weaponry are no match for the combined forces of military, police and paramilitary groups, say independent security analysts.

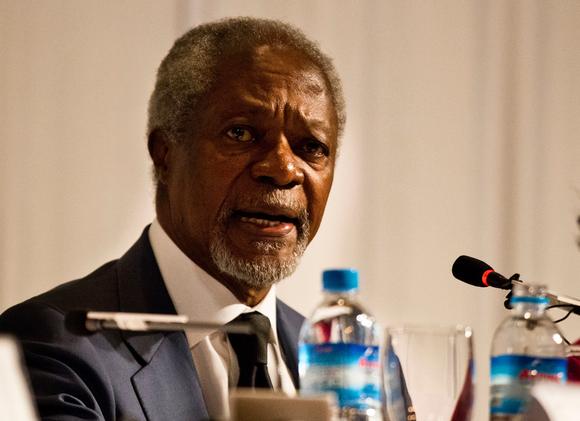

Former U.N. Secretary General and Chairman of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State Kofi Annan talks to journalists during a press briefing on the final report on the region on Aug. 24. © AP

In one measure that earned her some international approval and deflected external pressure, Suu Kyi last year appointed an advisory panel on Rakhine state headed by former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan. The commission’s 88 proposals included recommendations to consider citizenship for most Rohingya and basic rights such as freedom of movement and equal access to healthcare and education.

The report, launched the day before the Aug. 25 attacks, enraged the military, according to Yangon-based analysts. It is not known whether the ensuing attacks were linked to the report’s launch, but the military’s agitation no doubt added an edge to its harsh response — described by some analysts as an “ethnic cleansing operation” — launched after the attacks.

From zero to hero

Domestically, with popular resentment against the Rohingya rooted in Myanmar’s troubled history, even Suu Kyi’s silence in the face of military excesses is seen as favoring the widely detested minority, while internationally it has been portrayed as concurrence with the military’s campaign.

Indeed, in a mirror image of international criticism, the state counselor has drawn barbs from Myanmar’s overwhelmingly Buddhist population for being “too soft” on the threat from Rohingya militants. Mindful of such sentiments, she has generally avoided speaking out on issues related to Myanmar’s minority Muslim community — and did not select a single Muslim candidate to run under her National League for Democracy banner in the 2015 elections. The issue of stateless Rohingya Muslims — widely seen among the majority Buddhist Bamar population as interlopers from Bangladesh — has been one of her biggest “no-fly zones” since she took power early last year, according to Western diplomats.

Adding to growing internal tensions, Yangon tea shops have buzzed in recent days with rumors that the military, emboldened by its escalating campaign in northern Rakhine and alarmed that Suu Kyi might cave in to international pressure to curb the operations, could take a more provocative stance — or, in the most extreme scenario, seize power. That scenario, in the words of one senior Western diplomat, “is not as outlandish now as it would have been a year ago.”

Another great irony emerging from the Rakhine crisis is how the military has managed to partially cleanse its stained image since ARSA launched its first attacks last October. Through a relentless scare campaign over the threat of Rohingya radicalization and their portrayal of ARSA as a sophisticated transnational terrorist organization, military commanders have rallied the overwhelmingly Buddhist country behind an institution once reviled for its harsh rule and abundant human rights violations.

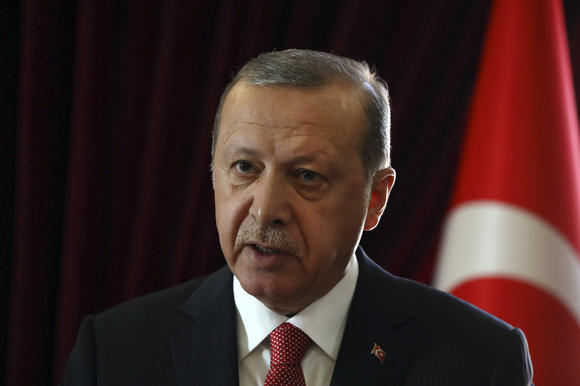

Equally incongruous is the extraordinary confluence of international protests against the Rohingya exodus and reports of military abuses. International concern and revulsion at images of fleeing civilians and reports of abuses have brought together Western governments, international organizations including the United Nations, and Islamic countries, led by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has called on his Muslim colleagues to support the Rohingya. In a further twist, Erdogan himself stands accused by human rights groups of widespread rights violations in his sweeping crackdown on the Islamist Gulen sect and Kurdish militants, particularly since last year’s coup attempt.

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan © AP

On the diplomatic front, the biggest short-term challenge for Suu Kyi’s government will come later this week with the start of the U.N. General Assembly in New York, and inevitable moves by some countries to censure Myanmar. The U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres recently warned of a looming “humanitarian catastrophe” while Britain — Suu Kyi’s long-time supporter, pushed for discussion of the Rakhine crisis in the U.N. Security Council.

Echoes of history

At the heart of the military’s growing paranoia in northern Rakhine is an old grudge dating back to earlier unrest among Rohingya Islamist movements — from the late 1940s through to the 1990s. Those grudges reignited waves of violence from 2012, under the reformist government of former President Thein Sein. More recently, military concerns were rekindled by the appearance of the ARSA fighters.

The key to military thinking on the Rohingya issue lies in Min Aung Hlaing’s recent pronouncements and the military’s brutal “four cuts” strategy employed against Karen ethnic fighters and communist guerrillas from the late 1940s onward. The four principles, or “cuts” are to deny insurgents food, funds, intelligence and recruits by ringfencing or moving whole communities. The strategy plays perfectly into the military’s — no doubt genuine — belief that the Rohingya insurgency is a grave threat that must be immediately eradicated.

In a rare briefing for select local media on Sept. 1, the commander-in-chief outlined his view of the ARSA threat, citing intelligence reports that the group had been steadily implementing a strategy to recruit at least one member in “every household” in northern Rakhine, and to achieve an independent state.

From the group’s limited media contact and investigations by independent local and international researchers, there are strong indications it has connections with Rohingya emigres in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan.

Despite military claims that the group has a separatist agenda and has trained its sights on all Buddhist communities, ARSA in its rudimentary media communications has stressed — at least for now — that its aim is to draw attention to the Rohingya plight. It claims to target government security forces, not civilians, although the group is widely believed to have killed dozens of suspected informers in Rohingya villages. ARSA has not detailed its ultimate aim, although Suu Kyi’s National Security Advisor Thaung Tun has echoed military concerns about the group’s alleged separatist agenda.

Whether by design or chance, ARSA’s desperate acts, carried out by a ragtag force with the crudest of weapons, triggered exactly the kind of ferocious military response against the broader Rohingya community that will help the movement gain international profile and sympathy, say some security experts.

“Certainly, at the moment, the ARSA are an indigenous organization with limited capabilities, they lack training, experience, resources, they are using rudimentary weapons and explosives,” said Phill Hynes, head of political risk and analysis at Intelligent Security Solutions, a Hong Kong-based security group.

“They’re not sophisticated in the slightest in an operational/military capacity. The sophistication comes in the rationale behind launching the attacks — to provoke precisely the response they got. You could say that we’re at the point where it could easily move from a low level, ethno-nationalist insurgency to a burgeoning radicalist campaign with greater momentum — a focal point for the forces of radicalization.”

On top of sympathy from the broader Islamic world, there are signs that ARSA has been drawing interest from other extremist groups in Asia and beyond, possibly as a useful platform to extend their own regional agendas, noted Hynes.

“This phase of the group’s push is a watershed, you could say it’s both a lightning rod and catalyst for commonality of purpose for radicals across the Asian region. These kind of forces want to open a new front in the global jihad, and the Rohingya are merely a pawn in the strategy.”

Looming behind the downward spiral of Rakhine state and Myanmar’s international image is the powerlessness of Suu Kyi, once the great hope for her country’s future, and the international community to influence the situation. The best the Bangladesh foreign minister could do in a weekend briefing to diplomats was to call on all governments and international organizations to provide urgent humanitarian assistance to address the current crisis.

The Bangladesh government has also asked the international community to urge the Myanmar government to implement the recommendations of the Annan commission report “in its entirety.” But with the report’s recommendations to facilitate citizenship for Rohingya, freedom of movement and other rights, that possibility is as remote as prospects for reconciliation between the two sides and the return of hundreds of thousands of refugees.

In the eyes of both supporters and critics of Myanmar’s stance, neither is ever likely to happen.

Perhaps the greatest irony of all is already taking shape: With more than 300,000 Rohingya having fled Myanmar since Aug. 25 alone, adding to an estimated 400,000-plus already living in squalor inside Bangladesh, Myanmar’s military has moved closer to achieving what it wants. And the ones to pay the price — along with neighboring Bangladesh — are Suu Kyi, the country as a whole and more than a million stateless Rohingya Muslims.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism

Myanmar’s de facto leader takes the flak in uneasy military relationship

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

INTERVIEW:

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations

Looking at the Rohingya crisis and beyond, Myanmar’s leader discusses issues facing her government

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her? – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

REPORT ON HER BIG SPEECH

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her?

Myanmar’s state counselor treads cautiously along a precarious line

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Economic and business implications:

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook

Looming ‘humanitarian catastrophe’ dampens international relations, business sentiment