Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook

Looming ‘humanitarian catastrophe’ dampens international relations, business sentiment{1st Photo Caption: Members of the media visit a village in northern Rakhine State on a government-organized visit on Aug. 30. (Photo by Thurein Hla Htway)}

POLITICS

Economic and business implications:

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook

Looming ‘humanitarian catastrophe’ dampens international relations, business sentiment

By GWEN ROBINSON, Chief editor and YUICHI NITTA, Nikkei staff writer

September 5, 2017 10:00 am JST

BANGKOK/YANGON — In the shiny new shopping malls and trendy restaurants of Myanmar’s commercial hub of Yangon there is no sense of the fear and mayhem gripping the country’s western Rakhine state.

The only focus on what the United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres labeled an emerging “humanitarian catastrophe” are headlines and lurid photos emblazoned across local newspapers about threats to the country from a new “transnational Bengali terrorist organization.

“Bengali” is a term widely used in Myanmar to refer to the Rohingya minority Muslim community as interlopers.

The group, which calls itself the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, launched coordinated attacks on Aug. 25 that killed 12 government security personnel across some 30 police facilities and an army base in northern Rakhine. Nearly 80 crudely-armed militants died in the attacks, and the military claims to have killed nearly 380 “suspected” members in the ensuing days.

A member of Myanmar’s security forces escorts media on an organized visit to conflict areas in northern Rakhine State on Aug. 30. (Photo by Thurein Hla Htway)

Since then, “clearance operations” by security forces and paramilitaries have been in full force. The operations have included summary arrests, interrogations and executions, as well as the burning of hundreds of houses across at least 17 villages, according to satellite imagery released by Human Rights Watch. The violence and the torchings — which the military has blamed on the Rohingya themselves — drove more than 76,000 refugees into neighboring Bangladesh in just over a week.

Beyond the headlines, local media coverage of the Rakhine attacks and the ferocious military response has been approving, and either hostile or indifferent toward the plight of the Rohingya in this overwhelmingly Buddhist country.

In international circles, by contrast, the Rakhine crisis has drawn fresh condemnation of the government’s extreme response and has further eroded the image of the country’s de facto leader, State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi.

Suu Kyi, a Nobel laureate and former political prisoner, has been criticized by western media and human rights groups for failing to speak out during earlier waves of violence against the country’s Muslim minority — particularly after her National League for Democracy swept elections in late 2015.

In response, Suu Kyi appointed former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan in 2016 to lead a commission to investigate the problems of Rakhine State. His team’s recommendations, presented just before the Aug. 25 ARSA attacks in Rakhine, included 88 proposals including facilitating Rohingya citizenship applications and freedom of movement. A Western diplomat described most of the proposals as “untenable” for Suu Kyi to pursue in the current climate, “even if she wanted to — and we certainly don’t see any inclination right now.”

While her silence on the Rakhine crisis is seen as a political calculation to keep the mainly Buddhist population on her side, the latest Rohingya crackdown — unprecedented in its intensity and scope — could irreparably damage her international standing, already tarnished by her government’s crackdown on press freedom.

Myanmar State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi attends the funeral of Aung Shwe, former chairman of the National League for Democracy, in Yangon on Aug. 17. © Reuters

If there are further military atrocities and continuing refugee flows, Myanmar could well face international censure, including curbs or conditions on aid and investment in the country, warn some analysts.

Ironic reversal

For many who pinned their hopes for further democratization and economic reform on Suu Kyi’s government, the notion that Myanmar could again become a pariah state, isolated by the West for human rights violations, is as shocking as the international condemnation of the once widely admired leader.

For investors — both domestic and foreign — the main worry is about potential fallout on the business and investment outlook for Myanmar’s fragile economy, which is struggling to reach the 7-7.5% annual growth notched up under the preceding Thein Sein government.

Rakhine is ranked among the poorest of Myanmar’s 14 states and divisions — even though it hosts the vast majority of the country’s multi-billion dollar offshore oil and gas industry and most foreign exploration contracts. The coastal region around Kyaukphyu features the state’s crowning investment: the Chinese-funded, dual oil and natural gas pipelines stretching to Yunnan in southern China. Beijing is now negotiating to finalize its proposals for an industrial zone in Kyaukphyu, which it hopes to eventually connect to Yunnan by a railway. Elsewhere, the state features the pristine beach resort of Ngapali and the ancient former capital of Mrauk-U, as well as an Indian-funded port development in Sittwe, the state capital.

Rakhine is ranked among the poorest of Myanmar’s 14 states and divisions — even though it hosts the vast majority of the country’s multi-billion dollar offshore oil and gas industry and most foreign exploration contracts. The coastal region around Kyaukphyu features the state’s crowning investment: the Chinese-funded, dual oil and natural gas pipelines stretching to Yunnan in southern China. Beijing is now negotiating to finalize its proposals for an industrial zone in Kyaukphyu, which it hopes to eventually connect to Yunnan by a railway. Elsewhere, the state features the pristine beach resort of Ngapali and the ancient former capital of Mrauk-U, as well as an Indian-funded port development in Sittwe, the state capital.

Up to now, the Rakhine crisis has been seen more as the preserve of human rights campaigners and political analysts — not investors. Western governments — particularly the U.S. under Trump — are unlikely to revive sanctions. But growing international alarm about the extent of military brutality is fuelling anxiety that if it goes unchecked, the atrocities could shake investor sentiment and drag on economic growth.

“So far, I have heard of no companies looking to pull out as a result of the events in Rakhine,” said Peter Beynon, chairman of the British Chamber of Commerce Myanmar. “The more immediate negative impact is for those companies seeking to enter the market. The human rights issue gives managers already programed to say ‘no’ an easy reason to turn down the investment case.”

Few of the chamber’s British corporate members have operations in Rakhine, although some are involved in oil and gas exploration off the state’s coast. In general, the concern for big Western companies in the spiraling Rakhine violence is mainly reputational risk. The U.S. oil major Chevron, for example, is under strong pressure from activist investors to withdraw from its Rakhine based offshore exploration business.

“Investors do not need much these days to get spooked,” said Josephine Price, managing director of Anthem Asia, an independent investment and advisory group. “On the positive side, they need a ‘story’… The renaissance of Myanmar under [Suu Kyi] was the ‘story,’ but the new story is more like ‘more of the same old Asian mess,’ when it should be about the ‘Asian road to prosperity’.”

“Investors do not need much these days to get spooked,” said Josephine Price, managing director of Anthem Asia, an independent investment and advisory group. “On the positive side, they need a ‘story’… The renaissance of Myanmar under [Suu Kyi] was the ‘story,’ but the new story is more like ‘more of the same old Asian mess,’ when it should be about the ‘Asian road to prosperity’.”

“Companies always review the political and economic environments when making investment decisions,” noted Judy Benn, executive director of the American Chamber of Commerce (AMCHAM) in Thailand and Myanmar. “However to date, we’re not aware of any U.S. companies that have declined to do business in Myanmar because of the situation in Rakhine state.”

Regardless, AMCHAM Myanmar and its 170 or so member companies are “deeply concerned by any human rights violations, and we continue to stand firm on our universal business principles which encourage governments of the obligation to protect all human rights,” she added.

Even so, some companies are more concerned about reputational risk than others. A Yangon-based consultant gave the example of a North Asia-based apparel maker that is a key supplier for prominent U.S. labels. The company was planning to set up operations near Yangon, but shelved the plan as the Rakhine violence intensified: “They didn’t mind costs of roads or electricity, they were serious about [setting up] — but the violence has unnerved them about reputational risk. You can’t afford any vulnerabilities when you’re supplying U.S. multinationals,” he said.

A taxi driver working for Uber uses the Uber app in his car in Yangon, Myanmar.© Reuters

At the same time, there are still prominent Western names entering Myanmar, the best known among the current crop being rival taxi service companies Uber and Grab, and American food outlets Hard Rock Cafe and Burger King, which also opened this year.

Most investors and consultants believe the Rakhine crisis will not trigger old-style sanctions against Myanmar. “I don’t think that sanctions will come back as they have been proven so ineffective in the past,” said Luc de Waegh, head of West Indochina, a leading Myanmar-based consultancy. “The business climate here is currently not at its best for various reasons. Rakhine is just one factor.”

Overall, the Rakhine violence can only deepen the growing sense of unease about Myanmar’s once bright economic future.

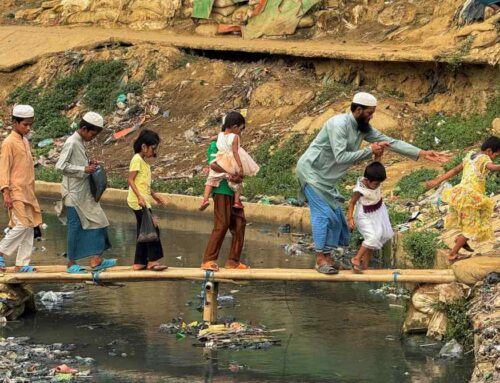

Rohingya refugees from Myanmar wait for food rations distributed by Bangladeshi volunteers near the Gundum area of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, on Sept. 3.© AP

But the impact on investors’ sentiment will be limited, “as foreign companies mostly focus in areas like Yangon,” said Hirokazu Yamaoka, managing director of the Japan External Trade Organization’s Yangon office.

Japanese companies are collectively among the top investors in Myanmar, although as they often invest through subsidiaries outside of Japan, the country only ranked as 11th largest investor in the fiscal year to March 31.

“We do not expect immediate impact from the Rakhine situation on investment in Myanmar,” said Katsuji Nakagawa, chairman of the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Myanmar. “My colleagues at the chamber agree with me that this issue cannot be solved overnight, as it is deeply rooted in people’s sentiment and their history. But it is also concerning, that if this situation continues it could damage the country’s international reputation. We don’t want to see democratization backslide because of this.”

While total applications for new investments have been robust, actual inflows of foreign direct investment slowed in 2016 to $2.1 billion from $2.8 billion the previous year, according to U.N. figures. That said, unless the Rakhine violence intensifies into an even more serious confrontation, the impact on the already subdued investment climate is likely to be minimal, said Eric Rose, lead director of Herzfeld Rubin Meyer & Rose, the first U.S. law firm to establish a Myanmar branch.

“Most of the incoming new foreign investment, already at reduced rates, is coming from Asian countries, which are less sensitive to human rights issues,” he noted.

The country’s nascent tourism industry, however, remains vulnerable, said Edwin Briels, managing director at Khiri Travel Myanmar.

“In Rakhine State a big part of the problem is about not getting out the right information,” he noted. “If you look at the image of Myanmar, for many people it is either dangerous or boring, because when you Google ‘Myanmar,’all you see is temples, and when you Google ‘Myanmar news’ you only see Rohingya news,” he said.

Additional reporting by Peter Janssen, contributing writer

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism

Myanmar’s de facto leader takes the flak in uneasy military relationship

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

INTERVIEW:

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations

Looking at the Rohingya crisis and beyond, Myanmar’s leader discusses issues facing her government

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her? – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

REPORT ON HER BIG SPEECH

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her?

Myanmar’s state counselor treads cautiously along a precarious line

Myths and realities behind the Rakhine crisis – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

A BACKGROUNDER, “Myth and realities behind the Rakhine crisis”

Condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi highlights ironies of Myanmar’s recent history