Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her?

Myanmar’s state counselor treads cautiously along a precarious line{1st Photo Caption: Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi speaks during a televised national address in Naypyitaw on Sept. 19. (Photo by Shinya Sawai)}

POLITICS

REPORT ON HER BIG SPEECH

Aung San Suu Kyi speaks, but does the world believe her?

Myanmar’s state counselor treads cautiously along a precarious line

GWEN ROBINSON, Chief editor

September 19, 2017 10:56 pm JST

NAYPYITAW — The staging of two very different meetings in the gleaming, Chinese-built convention center in Myanmar’s capital, Naypyitaw, on Tuesday highlighted an incongruous disconnect over the escalating refugee crisis in western Rakhine state and the “business as usual” mood in the country’s big cities.

In one hall, top diplomats and representatives of international organizations crowded in to hear the first public comments by de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi on the exodus of more than 410,000 stateless Muslim Rohingya refugees into neighboring Bangladesh amid a harsh military crackdown. In the hall next door, hundreds of business executives gathered for an annual technology and telecommunications conference to hear about new opportunities in the country’s hottest investment sector.

While they seemed light years apart, it is the relationship between fragile investor confidence in Myanmar, domestic hostility to the Rohingya community’s plight and growing international alarm over Myanmar’s deteriorating human rights record that finally prompted Suu Kyi, as state counselor, to address the Rakhine issue. The timing of the speech was broadly intended to substitute for her long-planned appearance at the United Nations General Assembly, which opened on Sept. 12 in New York. One of her two vice presidents, Henry Van Thio, is scheduled to address the assembly on Wednesday, but Suu Kyi is clearly aware that the world wants to hear from her.

Amid escalating international condemnation of widely reported human rights abuses and the mass exodus of Rohingya from Rakhine, Suu Kyi opted to deliver an address to a mixed local and international audience which featured ambassadors and Patrick Murphy, the visiting U.S. deputy assistant secretary of state for Southeast Asia, as well as scores of Burmese officials and individuals. Murphy, who planned to visit Sittwe, the Rakhine state capital, during his brief visit, said he would need time to “digest” Suu Kyi’s speech before any official comment.

Members of the media visit a village in northern Rakhine state on a government-organized tour on Aug. 30. (Photo by Thurein Hla Htway)

The U.S., like most Western countries, is in an awkward situation. Having wholeheartedly supported Suu Kyi in her long years as a political prisoner under an earlier military regime, and backed her party’s bid for election in 2015, many Western governments feel there are few alternatives to her leadership — even though they praised the reform efforts of former President Thein Sein and his administration from 2011-16.

That commitment has wavered since the brutal military campaign unleashed by attacks on Aug. 25 by a militant group calling itself the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army on about 30 police posts and a military facility in northern Rakhine.

The military’s so-called “clearance operations” in the aftermath, aimed at rooting out terrorists, have seen nearly 100 villages razed or severely damaged, hundreds of deaths and the refugee exodus amid reports of torture, summary arrests and executions. And they have drawn harsh condemnation of Suu Kyi by international figures, from fellow Nobel laureates to U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Like many others, they have implored Suu Kyi to speak out and act “within her powers” to halt the carnage in northern Rakhine. Having accused Suu Kyi of abandoning her principles, few have acknowledged her diminished status as de facto leader, barred by constitutional restrictions from the presidency, and with no constitutional power to direct the military.

Asserting that at least 50% of Muslim villages in Rakhine state remain “intact,” she questioned aloud the dynamics of northern Rakhine that had prompted so many to flee, and invited members of the diplomatic and international aid community to visit the state and see the “many” areas where Muslims and Buddhists live peacefully side by side.

A Rohingya refugee girl reacts to the camera as she is temporarily held by the Border Guard of Bangladesh in an open area after crossing the border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh on Sept. 3.© Reuters

In further efforts to rebut international criticism of the military campaign, Suu Kyi in her speech condemned “all human rights violations” in the state. In overwhelmingly Buddhist Myanmar, the abuses have been blamed almost solely on “Bengali terrorists,” a widely used term that implies the Rohingya are interlopers. Local media coverage meanwhile has focused on the displacement of an estimated 30,000 Rakhine Buddhists.

In comments clearly aimed at her international audience, but which are bound to fuel further domestic pressure for a tougher stance on the anti-terrorist campaign in Rakhine, she said that her government was ready to allow repatriation of refugees from Bangladesh.

Pledging commitment to the “restoration of peace and stability and rule of law” throughout Rakhine state, she said action would be taken “against all people regardless of their religion, race and political position, who go against the law of the land and violate human rights.”

Tightrope act

Suu Kyi’s speech attempted overall to tread a perilously thin line between starkly opposing views among domestic and international audiences. It was hardly surprising, noted some observers, that she met a mixed response from the audience.

Most foreign representatives applauded her pledges such as her commitment to punish human rights violations; begin a process of refugee repatriation; “any time;” implement recommendations of an advisory commission chaired by former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan; and invite diplomats and aid officials to visit sites in Rakhine. But some foreign officials said they had hoped she would go further to address directly the accusations of ethnic cleansing.

Top diplomats and representatives of international organizations listen to Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi in Naypyitaw. (Photo by Shinya Sawai)

Various U.N. officials have branded the military operation in Rakhine as “ethnic cleansing.” Suu Kyi did not address that accusation but said her government was ready at any time to allow repatriation of refugees under a 1993 agreement with Bangladesh, in which the criteria for return focused on the ability to provide bona fide indications of prior residence in Myanmar.

However, her assertion that there had been “no armed clashes” and no [military] clearance operations since Sept. 5″ drew angry responses from some international organizations — including officials from aid agencies working in northern Rakhine.

“You only need to look at the daily reports since Sept. 5, the billowing smoke, the relentless destruction of villages and continuing refugee flows to know that this is patently untrue,” said one Western aid official. Some diplomats said the statement was misleading at best, or disingenuous at worst. Unintentionally or otherwise, it also disguised the rampant mob violence by Rakhine Buddhist groups against Rohingya communities and, on a more sinister level, the growing use of civilian paramilitary groups widely believed to be recruited and armed by the government’s security forces, some noted.

Since Sept. 5, satellite images released by Human Rights Watch have shown military vehicles near burning villages, suggesting complicity if not direct culpability.

“The most obvious conclusion is that she was simply conveying what she had been told by the military, or that she was deflecting heat from them — neither is very palatable,” remarked one Western diplomat.

For Myanmar’s majority Burman people, who could watch the speech live on national television, the sight of their leader speaking in English drew some questions and complaints on Myanmar’s overactive social media. But among those present at the speech, her promises sent a balanced message, according to Denzil Abel, a Burman adviser to international aid organizations.

“It was a message of peace, it was both a call to get our act together and an appeal to all sides to draw back from fear-mongering and hate speech, though she was clearly being careful not to step on toes,” he said.

Aung San Suu Kyi walks to a podium before her speech in Naypyitaw on Sep. 19. (Photo by Shinya Sawai)

“Yes it raised difficult issues, but it was overall a message that she wants peace and she wants people to join and support,” said Rose Swe, CEO of Mango Media, a public relations company. “I don’t think she will be condemned domestically — not all people in this country are [opposed] to those suggestions, there are many knowledgeable, intelligent people who would support that message.”

In international eyes, while Suu Kyi can be commended for speaking out on some issues, the speech fell far short of high expectations, noted Richard Horsey, a veteran independent analyst on Myanmar. “This was a speech designed for a podium at the U.N. General Assembly, not as a detailed action plan to brief Myanmar’s international community — in that respect it didn’t really meet the expectations of the numerous skeptics,” he told the Nikkei Asian Review.

On the other hand, many in the West still feel there is no alternative to Suu Kyi, and that she has been wedged by the Rakhine crisis. “In that respect she will still have some measure of support and understanding,” he added.

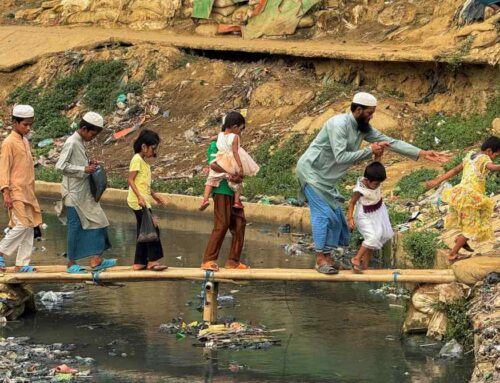

The key question for many in the international community is the fate of the 410,000-plus refugees living in squalid conditions with scant food and almost no medical attention on the Bangladesh border. They join at least 350,000 Rohingya refugees who fled to Bangladesh amid earlier waves of violence in Myanmar. With international aid agencies overstretched and Bangladesh insisting it has no capacity to host more refugees, time is running out.

“There is simply nowhere for them to go — nobody wants them, but when they start dying in droves, this is going to become Myanmar’s problem as much as Bangladesh and international organizations,” said an aid official after the speech, The irony, noted several others in the audience, is that all efforts by Suu Kyi and her government to reverse the international condemnation could come to nothing if there are mass deaths among refugees.

Even so, repatriation “is a conversation for another day,” said Horsey. “First the conditions must be established for a safe, dignified and voluntary return. At the moment, people are still fleeing and villages are still burning.” Several aid officials said that halting the violence and allowing independent humanitarian support on both sides of the border should be the immediate priorities.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Aung San Suu Kyi remains unbowed under criticism

Myanmar’s de facto leader takes the flak in uneasy military relationship

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

INTERVIEW:

Aung San Suu Kyi defends policies, points to broader investigations

Looking at the Rohingya crisis and beyond, Myanmar’s leader discusses issues facing her government

Myths and realities behind the Rakhine crisis – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

A BACKGROUNDER, “Myth and realities behind the Rakhine crisis”

Condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi highlights ironies of Myanmar’s recent history

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Economic and business implications:

Rakhine crisis blights Myanmar economic outlook

Looming ‘humanitarian catastrophe’ dampens international relations, business sentiment