Religious extremism poses threat to ASEAN’s growth

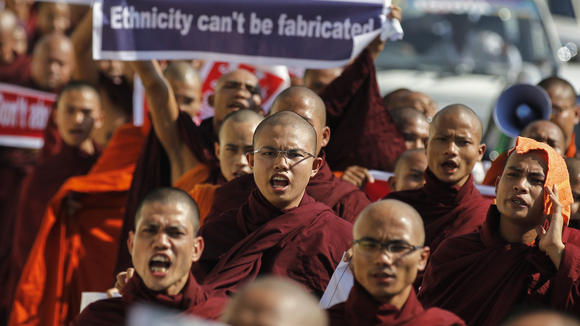

Aided by social media, hardliners gain mainstream support{1st Photo Caption: Buddhist monks protest the visit of a U.N. official in Yangon on Jan. 16, 2015. According to local media reports, they were angry that the international organization had urged the government to give members of the Rohingya minority citizenship. © Reuters}

THE BIG STORY

Religious extremism poses threat to ASEAN’s growth

Aided by social media, hardliners gain mainstream support

GWEN ROBINSON, Chief editor, and SIMON ROUGHNEEN, Asia regional correspondent

December 13, 2017 3:14 pm JST

YANGON/JAKARTA — With Mt. Agung billowing volcanic ash into the sky above his home in Bali, Khairy Susanto was unsure if he could fly back after joining tens of thousands of fellow Indonesian Islamists at a rally near the presidential palace in Jakarta.

“Inshallah, we can fly, but it doesn’t matter, we will be OK,” Susanto said. “We are happy to be here today to celebrate our victory.”

The Dec. 2 event marked a year since an estimated half-million people clamored in the rain for the arrest of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, the then-governor of Jakarta. Since then, Purnama, a Protestant of Chinese descent nicknamed Ahok, lost the gubernatorial election and was sentenced to two years in jail on the same blasphemy charges that brought massive crowds onto Jakarta’s streets late last year.

The episode raised concerns around the world that Indonesia’s relatively tolerant variant of Islam — and its secular democracy — was under attack. And it was a startling display of the strength of Islamist groups in Indonesia, home to the world’s largest Muslim population. Among the organizers were the Islamic Defenders Front, known as FPI, and the Islamic Ummah Forum.

Members of the Islamic Defenders Front protest the accession of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama — an ethnic-Chinese Christian nicknamed Ahok — as governor of Jakarta in November 2014. The sign reads “Ahok is the enemy of Islam.” © Reuters

Those groups do not claim affiliation with the al-Qaida-linked militants who killed 202 people in Bali in 2002, nor the estimated 1,150 Indonesians who traveled to Syria and Iraq to fight for the so-called Islamic State. But the government has been sufficiently alarmed to ban the local wing of Hizbut Tahrir, another Islamist movement involved in the anti-Ahok protests — and which hopes to establish a caliphate.

Across Asia, the rise of hard-line religious movements is fueling a macho form of nationalism and creating dangerous new fault lines in communities. Beyond Indonesia with its numerous Islamist groups are Myanmar’s zealous Buddhist organizations, which have stoked anti-Muslim sentiment to deadly effect. Bangladesh has seen the rise of Islamic fundamentalists including Hefazat-e-Islam, while Sri Lanka has Bodu Bala Sena, a radical Sinhalese Buddhist group.

Such groups number in the dozens across Asia — fundamentalist Buddhists, Muslims and Hindus who are adding new fuel on what are sometimes ancient ethnic conflicts. Some boast memberships that run into the hundreds of thousands, powered by zealous social media campaigns, community support programs and effective fundraising operations. The donations, often tiny amounts collected from poor followers, become a source of support for hard-line leaders.

An armored personnel carrier transports troops in the southern Philippine city of Marawi in October. Earlier that month, military forces ended a five-month siege of the city by Islamic State-linked militants. © Reuters

Analysts warn that such ethno-religious chauvinism represents the biggest threat to the economic growth the region has enjoyed in recent years — and to the dream of greater cohesion over trade and economic issues. “Rapid economic growth over the past three decades has raised standards of living across much of Asia, but left marginal areas, like Mindanao in the Philippines and Rakhine State in Myanmar, untouched and therefore comparatively worse off,” said Michael Vatikiotis, Asia director of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. “It is perhaps no coincidence that these areas are afflicted by violent conflict.”

Vatikiotis warns that rising levels of economic inequality and bitter political divisions could fan a broader conflict in mainstream society. Unlike IS and other jihadist groups, these groups focus more on protests, propaganda and, in extreme cases, physical intimidation. Through networks of community-based leaders, they bring in funding and support from relatively moderate constituencies.

Some hard-line groups are connected to more constructive religious and community-building activities, noted Matthew J. Walton, a Myanmar specialist at Oxford University’s St. Antony’s College. Myanmar’s Buddhist nationalist movement is made up of a complicated mix of people and groups “operating in an opaque environment that blurs religious and political motivations,” Walton said.

Ma Ba Tha, also known as the Buddhist Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, has a nationwide base of monks and lay-members numbering in the hundreds of thousands. But it has also become a crucial source of support for hard-line monks, even as it insists it seeks to protect Buddhist principles of peace and harmony.

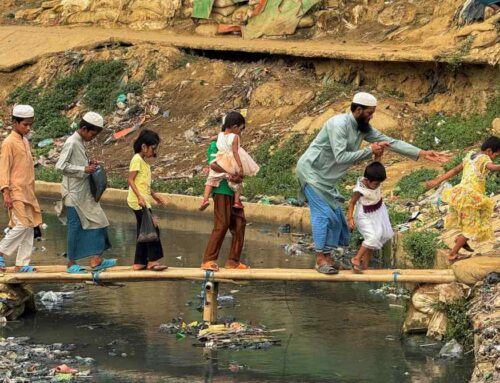

The group is said to have raised the equivalent of $3 million to help Buddhist communities in western Rakhine within weeks of attacks by Muslim militants in October 2016 and August 2017. Those attacks were met by a ferocious military response that resulted in the exodus of more than 800,000 Rohingya Muslims into Bangladesh amid reports of shocking abuses.

Myanmar does not accept the existence of a Rohingya identity, with the majority Burman Buddhists labeling them “Bengal” interlopers. There are entrenched perceptions that the broader Muslim population — which officially totals less than 5% — has grown at the expense of Buddhists, particularly in Rakhine State. Groups such as Ma Ba Tha began fanning such notions when Myanmar started implementing democratic reforms in 2011.

Broadly, the group’s agenda “speaks to the widespread embrace of Ma Ba Tha’s guiding ideology — specifically, that Buddhism is under pressure from external and internal forces,” said Melyn McKay, an academic researcher into women’s participation in Myanmar’s religious movements.

A Rohingya girl waits to cross into Bangladesh outside the border fence at Maungdaw, in Myanmar’s western Rakhine State, in September. © Getty Images

“Jakarta is ours”

In Indonesia, the situation is reversed, with Islamist hard-line groups targeting Christians, Chinese and other minorities. The demonstrations paid off for Purnama’s political opponents, with the Muslim former Education Minister Anies Baswedan beating the incumbent in an April run-off election.

Acknowledging the role the anti-Ahok demonstrations played in his victory, Baswedan paid tribute during the Dec. 2 rally, telling his Islamist supporters: “Jakarta is ours. It doesn’t only belong to some of us,” presumably meaning minority religions and other ethnicities.

Baswedan, who is of Yemeni descent, gave a divisive inaugural speech, invoking the rights of “pribumi” or “native” Indonesians — a dog-whistle message that contradicted Indonesia’s national motto “Unity in diversity.”

The vitriol espoused during the 2016 demonstrations — some banners demanded Purnama’s execution — evoked memories of the 1998 demonstrations that ended three decades of Suharto dictatorship. That uprising was marred by racist riots against Indonesia’s ethnic-Chinese minority.

“It is better for us that [Purnama] serves his sentence. There will be less anger and threats to us,” said a Chinese-Indonesian professional.

The ousting of Ahok suggested that mainstream opponents of President Joko Widodo saw benefit in hopping on an Islamist bandwagon ahead of the 2019 national elections. Widodo’s political opponents see the chance to challenge him over contentious identity politics. “They try to play the similar tactics and prepare for the next election,” said Bonar Tigor Naipospos of the Setara Institute, which tracks religion and politics in Indonesia.

Hard-line Islamist groups such as FPI are on the front foot, emboldened not only by their success in ousting Purnama, but also by the growing acceptance by mainstream politicians.

Baswedan “weaponized” the blasphemy issue and made the FPI more powerful, says Boston University’s Jeremy Menchik, author of “Islam and Democracy in Indonesia: Tolerance without Liberalism.” But there is no indication that political Islam along the lines of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood — much less any kind of Taliban Nusantara — is about to vie for power in the country. The Indonesian government simply wants stability and an Islam sufficiently apolitical that it is of little concern to foreign investors already bothered by poor infrastructure and governance.

In Myanmar, the government led by Aung San Suu Kyi is also craving stability. The council, or Sangha, temporarily banned Ma Ba Tha’s affiliated extremist monk Wirathu from delivering public sermons this year. The group’s name change in May to the Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation was aimed at sidestepping a separate order by the Sangha to disband.

Ultranationlist monk Wirathu, leader of Myanmar’s hard-line Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation, is an outspoken opponent of Islam. © Reuters

Even so, the activities of Myanmar’s self-proclaimed patriotic monks are constrained by rules against participating in politics, unlike the Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka, which hosts a particularly aggressive strain of Theravada Buddhism — personified by Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist Force/Army), led by outspoken monk Galogadaththe Gnanasara.

Its growing appeal among Sri Lankan conservatives has seen Buddhist monks move into national politics. In the 2004 parliamentary elections, a new, Buddhist-dominated party, Jathika Hela Urumaya (National Heritage Party), fielded an entire slate of monks. Nine were elected to the 225-member legislature — a first in Sri Lanka. The spectacle of Buddhist monks winning parliamentary seats puts Sri Lanka’s version of Theravada in a different league than its counterparts in Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos. In signs of growing militancy, monks have led attacks on Rohingya refugees in the Sri Lankan capital, Colombo, while Buddhist groups have vowed to drive Rohingyas out of the country — a sentiment echoed in parts of Hindu-majority India.

“Pitted against each other”

Ultimately the spread of a more militant ethno-religious chauvinism could hit both economic growth and stability in an increasingly affluent Asia.

Southeast and East Asia rank behind regions such as the Middle East in militant attacks over the last 15 years, according to the 2017 Global Terrorism Index compiled by the Sydney-based Institute for Economics & Peace. In 2017, however, the Marawi siege in the southern Philippines and the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar suggest that Southeast Asia will figure more prominently in the next round of calculations.

In many ways, these events cracked open religious fault lines like never before within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, said Kavi Chongkittavorn, a senior fellow at the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

“About 60% of the ASEAN population of 640 million or so is Muslim, with Buddhists dominating in five countries [Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam] and more than 110 million Christians in the Philippines. When leaders focus on say, the plight of Rohingya Muslims, it can easily pit these religious communities against each other,” he said.

The Myanmar military’s recent drive against the Rohingya minority, meanwhile, appears to have revived its domestic public image, which had long been tarnished by its record of human rights abuses against dissidents and other ethnic groups. More mainstream Buddhist leaders, meanwhile, have started to adopt some of the chilling rhetoric espoused by Ma Ba Tha and its antecedent 969 movement, which rose after Myanmar dispensed with military rule after 2011.

Rohingya refugees cross the Naf River at the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Palong Khali, near Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, in November. © Reuters

At the same time, the plight of the Rohingya has galvanized the Muslim world and prompted al-Qaida, Islamic State and other jihadist groups to call directly for attacks on Myanmar and its leaders, noted International Crisis Group in a recent report. “Myanmar is not prepared to prevent or deal with such an attack, which could be directed or merely inspired by these jihadist groups,” and lead to fresh waves of communal violence, it said.

The more immediate concern, however, lies in the overcrowded camps around Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, near the Myanmar border. The big question among security analysts is about the potential for Rohingya radicalization in the camps, and whether this should be the next big regional security concern. Leaders of the militant Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, which launched attacks on security forces last October, have urged followers to “martyr” themselves, while insisting they have rejected overtures from international jihadist groups.

“Having more than 600,000 people confined in the largest refugee camp in the world, traumatized and with no hope for the future, carries many risks — including risks of recruitment into militant groups such as ARSA, as well as radicalization and recruitment by more dangerous Bangladeshi and transnational Islamist groups,” said Richard Horsey, a Yangon-based consultant. Unlike IS supporters who dream of a new Islamic caliphate in Asia, most Rohingya — if they think about issues beyond day-to-day survival — are calling for citizenship and rights to live in Myanmar, he noted.

Rohingya and Bangladeshi migrants collect rainwater at a refugee camp in Myanmar’s Rakhine State in 2015. They were rescued from a boat carrying 734 people off the southern coast. © Reuters

Even so, security experts who advise regional businesses and governments have a more pessimistic view. “The potential for further radicalization across the region has never been higher,” said Phill Hynes, head of political risk and analysis at ISS Risk, a Hong Kong-based consultancy. “I’d say we’re at a tipping point in terms of the scaling-up of the Rohingya situation.”

The real danger, according to the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue’s Vatikiotis, lies in the hard-line attitudes and neo-nationalist agendas taking hold among some mainstream religious groups. “It’s time to stop the spread of these dangerous religious divides before they infect broader swathes of society,” he said. “But with elections looming across the region in the next several years in some of the most affected countries, such as Indonesia and Myanmar, it seems likely the problem will only grow worse.”

Asia regional correspondent Marwaan Macan-Markar contributed to this report.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Article:

Ugly social media wars fueling intolerance in Asia – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Ugly social media wars fueling intolerance in Asia

Similar tactics are cropping up across different areas and different faiths