Myanmar: Inside the coup that toppled Aung San Suu Kyi’s government

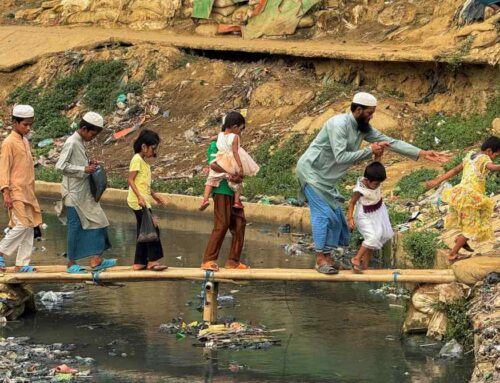

Ending civilian rule is a test for Washington — and a chance for Beijing{1st Photo Caption: After days of stop-start threats by the military, on Feb. 1 the government of Myanmar silently and seamlessly changed hands, without a shot. (Photo by Shinya Sawai)}

The Big Story

Myanmar: Inside the coup that toppled Aung San Suu Kyi’s government

Ending civilian rule is a test for Washington — and a chance for Beijing

GWEN ROBINSON and YUICHI NITTA, Nikkei staff writers, and THOMPSON CHAU, Contributing writer

February 3, 2021 06:42 JST

BANGKOK/YANGON/NAYPYITAW — Myanmar’s bloodless coup began with surgical precision in the pre-dawn hours of Monday as teams of soldiers detained the country’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. At the same time, the military was taking into temporary custody top officials of her National League for Democracy and about 400 lawmakers staying in the capital, Naypyitaw, for the first sitting of parliament since the Nov. 8 general election.

Internet and mobile phone communications were disrupted, and a statement read out on military television announced that the commander in chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing was now in charge. He declared a one-year state of emergency.

The move, according to the statement, was in response to fraud during last year’s election. With this, the government of Myanmar silently and seamlessly changed hands, without a shot. But the turmoil is just beginning.

The coup followed days of stop-start threats by military commanders to “take action” over their allegations of electoral fraud. The previous day, an unexpected assurance by Min Aung Hlaing that the military would “abide by the constitution” eased tensions that had been wracking the country since the election. Ironically, in taking power the military cited Section 417 of the constitution, which under some interpretations enables a military takeover under a “state of emergency.”

A military checkpoint in Naypyitaw, Myanmar’s capital, on Feb. 1. © Reuters

On Tuesday, a stunned but jaded country digested the reality. Suu Kyi had been under house arrest for 15 years over two decades to 2010, and now she was once again. Bizarrely, even as political leaders and activists remained in detention, calm prevailed in Naypyitaw and commercial hub Yangon. The internet and mobile communications were back up, banks were operating, and supermarkets and other businesses were open. Most people were socially distancing as the country continued to fight COVID-19, which has so far killed more than 3,100 and infected more than 140,000.

While armored vehicles could be seen around the capital at key government buildings such as the parliament compound and the presidential palace, there was no extra security at key ministries.

In Yangon, the initial mood of fear and shock steadily shifted to frustration and anger. “People still have the courage to get onto the streets. But I think they are still waiting for the NLD and pro-democracy forces for instructions. They don’t want to be accused of being a source of violence, if there’s any,” said a young resident of central Yangon who gave his name as Anthony.

Hours after the coup, Suu Kyi had issued a general call via Facebook — evidently prepared in anticipation of her arrest — for people to “protest” the takeover. By Tuesday, activists had taken matters into their own hands, most visibly on social media, where posts under the hashtag #CivilDisobedienceMovement called for a general strike and urged people to bang on metal pots and buckets.

The Ministry of Information warned against posting material that would “promote instability.” But at 8 p.m. Yangon roared with the din of clanging metal and loud shouts of protest. Highlighting popular opposition to the new junta, doctors and others at more than 40 government hospitals announced that they would stop working as “civil servants for a military junta” and try to help elsewhere to fight the pandemic.

Demonstrators hold up portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi and her late father, Maj. Gen. Aung San, during a protest at the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok on Feb 1. © Getty Images

A Yangon-based Asian investor was scathing about the coup and its leaders, echoing the sentiment of many foreign corporate executives in the country.

“Those who have put their money and faith in the Myanmar market are in for a shock. A key reason Myanmar is among the least developed in Southeast Asia is because of the ‘bonkers’ at the top,” he said, referring to the military leaders.

“The coup has blown the country’s trajectory entirely off course,” the investor said.

The more optimistic view suggests that some appointments to the new cabinet have been better than feared. In the first two days, the junta announced 19 cabinet posts and other key appointments via its military-run TV network, purging 24 of Suu Kyi’s ministers and deputies. Among the new appointees, many are from the administration of President Thein Sein (2011-16) and include a few respected technocrats.

But the overall mood is gloomy. Author and historian Thant Myint U, grandson of former United Nations Secretary-General U Thant, tweeted in response to the coup announcement: “The doors just opened to a very different future. I have a sinking feeling that no one will really be able to control what comes next. And remember Myanmar’s a country awash in weapons, with deep divisions across ethnic & religious lines, where millions can barely feed themselves.”

Political jujitsu

Even in the last five years under Suu Kyi’s NLD government, the military, or Tatmadaw as it is known, made little pretense of respecting civilian rule. The stiletto coup mechanism was sitting inside the 2008 constitution — a military-drafted document that set the stage for a discreetly planned transition to quasi-civilian rule.

Under a suite of constitutional provisions beginning with Section 417, Min Aung Hlaing was able to declare a state of emergency and take over legislative, judicial and executive powers indefinitely, although the coup announcement pledged elections after one year of emergency rule.

With its deviously worded sections that check and countercheck civilian institutions and power structures, the document enshrined the military’s hold by assigning it 25% of all seats in state and national parliaments and three key cabinet positions in defense and security. A 75% vote is required to change the constitution, effectively giving the military veto power. A provision that bars any Myanmar citizen with a foreign spouse or child has also kept Suu Kyi, whose children and late husband were British, from attaining the presidency — despite her broad recognition as the country’s de facto leader.

Aung San Suu Kyi walks to take the oath at the lower house in Naypyitaw, Myanmar’s capital, in May 2012. © Reuters

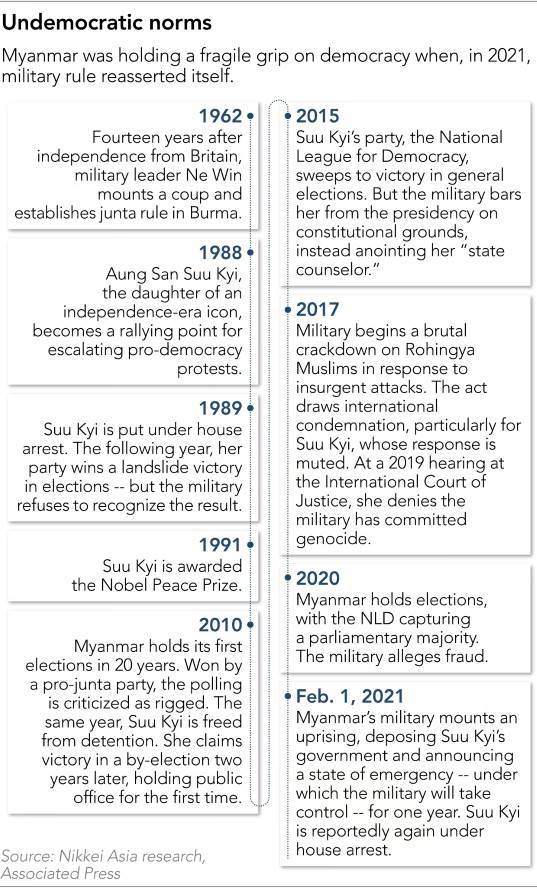

The military had many reasons to want a civilian figurehead while it held the reins of power. By 2010, after nearly five decades of military misrule and sanctions imposed by the European Union and the U.S., even the generals had recognized that the country was on the brink of collapse. Myanmar was an isolated pariah state, closed to most visitors, with a broken economy, almost no internet and harsh media censorship under a succession of repressive military governments — punctuated by two bloody military takeovers in 1962 and 1988.

Nearly half the population lived far below the poverty line. The kyat currency traded at more than 200 times the official rate on the thriving black market. And inflation in some years exceeded 30%, peaking at 57% in 2002. A SIM card even in 2011 cost upwards of $2,000, and cars were priced beyond the reach of most.

In 2010, junta chief Than Shwe abruptly announced his departure and elections and anointed a mild-mannered general, Thein Sein, as the candidate for the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party. Thein Sein’s predictable victory was greeted with cynicism by the West.

But following the release of Suu Kyi in 2010 and sweeping liberalization measures, he set the seal on a new reformist era. Myanmar’s pivotal moment in the last decade was the visit of Barack Obama in 2012 as the first sitting U.S. president to come to the country.

The brief but much-vaunted trip was a direct reward to Thein Sein’s quasi-civilian government for its reforms. By late 2013, three years into Thein Sein’s term, the country had witnessed dramatic changes to foreign investment, labor, telecommunications and media laws. Hundreds of political prisoners had been released, investment had flowed in, and the country had notched up 8.4% annual growth. Inflation was tamed, the kyat had stabilized thanks to a managed float, and mobile phone ownership and internet penetration had risen to nearly 100%. Nominal gross domestic product per capita rose to $1,608 in 2019, while poverty levels had been nearly halved from 48% in 2005 to just under 25%.

The military’s plans came unglued with Suu Kyi’s landslide 2015 election victory, which displaced most legislators from the military-backed USDP and handed her the opportunity to create a special role as state counselor and foreign minister. The following year, the U.S. began lifting nearly all sanctions against the country.

Much commentary in recent years has portrayed Suu Kyi as a “fallen angel” — an arrogant and power-hungry politician who betrayed her human rights supporters and presided over one of the greatest contemporary crimes against humanity: the military’s 2017 expulsion of more than 750,000 Rohingya minority Muslims from Myanmar’s western Rakhine state. She further infuriated supporters by going to The Hague in 2019 to defend the same military that had kept her in detention for years.

Top: Soldiers stand guard at a checkpoint on the way to the congress compound in Naypyitaw on Feb. 1, 2021, when the military launched its takeover. Bottom: Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, commander in chief of Myanmar’s armed forces. © Reuters

While supporters around the world saw Suu Kyi as a Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights defender, in reality she had always stressed law and order over social justice. As the daughter of independence hero Aung San, who was assassinated when she was just 2 years old, she grew up with a sense of entitlement and destiny. Through years of house arrest, she stuck grimly to her goal of following her father to become a national leader. At Oxford University she met British academic Michael Aris, whom she married and had two sons with. But from 1988, when she returned home to care for her sick mother and was caught up in that year’s bloody uprising, her life has been focused on Myanmar. In the heady, violent days of “8888” (August 8, 1988) Suu Kyi helped found the NLD with some aging activists and retired military officers who had turned against the armed forces.

Last November, her NLD delivered a humiliating defeat for the USDP, the military’s proxy party, which won just 33 seats against the NLD’s 396 seats in the national legislature, as many voters once again picked Suu Kyi’s camp as the best — and only — weapon to contain the generals.

Aung San Suu Kyi votes on Oct. 29, 2020, ahead of the Nov. 8 general election. © Reuters

To admirers, her accommodation of the army over the past five years was viewed by some as political jujitsu rather than appeasement. Ultimately, however, her resounding victory loomed as a threat to the ambitions of Min Aung Hlaing ahead of his expected retirement as commander in chief. Having extended himself for an extra five-year term at 65, the choices were limited and possibly involved becoming the military’s nominee for a guaranteed post as one of two vice presidents. The prospect of serving under a Suu Kyi-appointed president clearly held little appeal.

Chinese chess

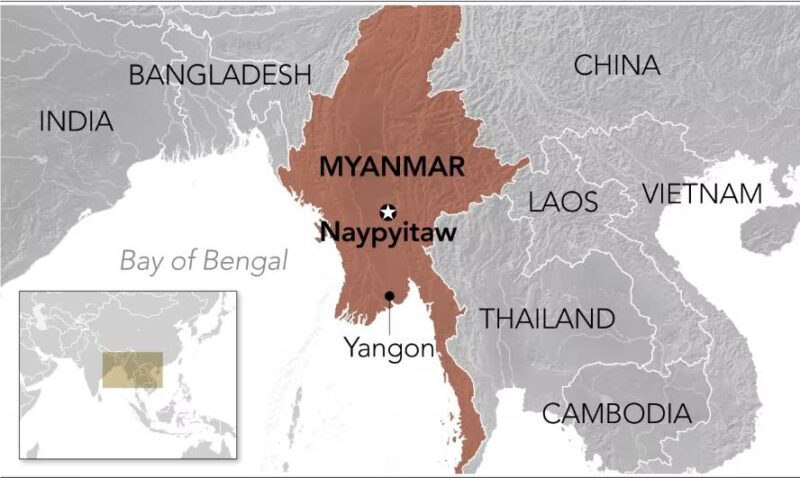

A British colony until 1948 and strategically located between China and India, Myanmar is again at the heart of an emerging Asian “great game” as rival powers compete for influence. By virtue of geographic fate, it falls into Beijing’s special category of “doorstep” countries, which, like Cambodia, Laos and 11 other countries bordering China, are of vital importance to its huge neighbor.

For decades, China was a close friend and protector for the pariah state — even more so when the West imposed sanctions from the 1990s — and a provider of military equipment and training, infrastructure investment, and other largesse.

But by the time sanctions hit Myanmar, the price of being a Chinese vassal state was palling on the generals, led by junta chief Than Shwe. Amid whispers of dissatisfaction over China’s controlling grasp, its involvement with Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups, its voracious appetite for the country’s natural resources, and its cheap but mediocre military equipment, the junta came up with a grand plan to rescue the failing economy and open up to the world. “We knew we had to diversify our relationships, open up, and that meant releasing Aung San Suu Kyi,” Thein Sein said in a 2012 interview. Nothing better illustrated the dissatisfaction than his abrupt suspension of China’s $1.4 billion Myitsone dam project in northern Kachin state, which remains on hold.

Even so, the bilateral relationship remains close. Min Aung Hlaing has been a frequent visitor to China, as have numerous senior officers and trainees.

Many observers feel there was no way Myanmar’s generals would have mounted a coup without alerting Beijing. The timing was coincidental, but it is significant that just weeks before the coup, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on a swing through Southeast Asia met with both the commander in chief and Suu Kyi in separate talks in Naypyitaw during his Jan. 12 visit to Myanmar.

According to one person familiar with their discussion, the military chief complained about election fraud. Wang responded that Myanmar’s military should play its “rightful” role and make a positive contribution to the country. He also talked of China’s hopes that the military would contribute to further improve bilateral relations. “How Min Aung Hlaing interprets all that is a different matter — he may have thought he was giving China notice,” said Yun Sun, director of the China program at U.S. think tank the Stimson Center.

She added: “How the U.S. and China deal with the aftermath of the coup will determine their relations with the country, as well as other dynamics in the region … but there is little chance China wants to be Myanmar’s sole protector.”

“China has been noncommittal and neutral, calling for restraint and stability, she said. “The U.S. has been more demanding, calling for reversing the coup, releasing detainees, and respecting the election. I don’t think any of these will happen, but China has more moral flexibility.”

Beyond the China dynamic, for new U.S. President Joe Biden, Myanmar’s coup presented an immediate challenge to his sweeping pledges to restore trust in American democracy. He responded accordingly, with a statement echoing his remarks after the Jan. 6 siege of Congress, saying: “In a democracy, force should never seek to overrule the will of the people or attempt to erase the outcome of a credible election.”

In a clear message to U.S. allies, and to Myanmar’s junta, he added that the U.S. would work with partner countries to “support the restoration of democracy and the rule of law.” More significantly, he signaled a willingness to reimpose U.S. sanctions removed over the past decade in recognition of Myanmar’s democratic progress. “The reversal of that [democratic] progress will necessitate an immediate review of our sanction laws and authorities, followed by appropriate action,” he said.

Some experts caution that sanctions are counterproductive. “Sanctions if anything delayed reform, decimated the emerging middle classes, reinforced isolationist and nativist tendencies, and created a context that makes any genuine progress towards democracy less likely,” Thant Myint U told Nikkei Asia.

“Sanctions may well have an effect of pressurizing the new regime, but at this stage, given severe economic distress and tens of millions facing acute poverty, they could also tip the country into widespread, perhaps uncontrollable, social unrest,” he said.

This time, any sanctions against Myanmar would come just as the country is reeling from the fallout from COVID-19 lockdown measures, including massive job losses in mainstay industries such as apparel manufacturing, seafood processing and tourism.

Others argue that the U.S. must act against the generals — not least for the credibility of the new Biden administration. Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, sees the Myanmar coup as an early test of Biden’s ability to restore a robust democracy policy. Biden is likely to “take pains to highlight” a break from the Trump administration, he noted. At the same time, other countries in the region, such as China, India and Japan, are the most important influential outside actors in the Myanmar context, he said.

“So I think [Washington’s] hands are tied,” Kurlantzick said.

The dilemma for Biden — and most likely for leaders of other Western countries that imposed sanctions against the previous military regime — is that reimposing curbs and isolating Myanmar could send the country back into China’s arms. Daniel Russel of the Asia Society Policy Institute said that the new U.S. administration is likely to “reject cynical realpolitik arguments about abetting the coup to avoid ‘losing’ Myanmar to China.”

“But the coup highlights the contrast between the Biden administration’s defense of democratic governance and the Chinese government’s embrace of authoritarianism,” he said. China’s support for the military junta will further complicate the task of de-escalating U.S.-China tensions, he warned.

Not so, say analysts such as Yun Sun. “People seem to assume China will benefit from better ties with the junta, but that doesn’t explain why back in 2010 the junta wanted to pursue democratic reforms, and reduce China’s overwhelming and exclusive influence over their country,” she said. “If the military government is isolated again by the international community, it will leave China as one of their few options, and I doubt China wants the liability associated with that.”

Kurlantzick, on the other hand, said U.S. sanctions on the main military companies could be a good idea, as well as a longer list of people targeted by asset control sanctions. Broad economic sanctions are unlikely though not ruled out, though such measures have been “tried before and they tend to hurt the people,” he said.

Compared with the determined U.S. reaction, the silence and jadedness emanating from Myanmar’s neighbors in Asia were taken as — short of tacit approval — a signal that there would not be much in the way of repercussions.

On Monday, the 10-country Association of Southeast Asian Nations (of which Myanmar is a member) issued a tepid statement that concluded: “We encourage the pursuance of dialogue, reconciliation and the return to normalcy in accordance with the will and interests of the people of Myanmar.” No repercussions for the coup leaders were mentioned.

Just three of 10 ASEAN member states issued individual statements of concern: Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. Thailand, which has the closest relationship with Myanmar and is led by a prime minister, Prayuth Chan-ocha, who seized power in a 2014 coup, dismissed the coup as a “domestic issue and internal affair.”

Even so, Biden has put cooperation with partner countries as a core theme of his foreign policy, bolstered by his appointment of Kurt Campbell to the new post of National Security Council coordinator for the Indo-Pacific region at the White House. As assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs in the first Obama administration, Campbell was a key architect of the “pivot to Asia” and the opening to Myanmar.

“He is aware of the futility of isolating Myanmar — two decades of sanctions did nothing to change the military’s behavior — and the continuing, indeed, even greater validity of the strategic considerations given the enhanced competition with China,” said Bilahari Kausikan, former permanent secretary of Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“ASEAN is an important and influential stakeholder that in the past played a significant role in inducing the Burmese military to loosen its grip and allow political reform,” Russel said.

Now more than ever, ASEAN needs to show the international community — particularly the new U.S. administration — that it can manage its internal troubles, said Kavi Chongkittavorn, senior fellow at the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

“Myanmar has been a perennial problem,” he said. “But regional inaction or any display of paralysis over such issues would further weaken the bloc’s much-vaunted principle of centrality, and possibly compel outside powers to exercise influence by various means.”

Additional reporting by Francesca Regalado in Tokyo, Dominic Faulder in Bangkok, Cape Diamond in Naypyitaw and Alex Fang in New York.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Failed state: Myanmar collapses into chaos – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Failed state: Myanmar collapses into chaos

A divided international response, a fractured country and a murderous regime

Myanmar, a violent tale of two governments – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Myanmar, a violent tale of two governments

A failed state plunges toward civil war

The Myanmar crisis – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Coups, couriers and COVID: The Big Story 2021 Hall of Fame

From the Tokyo Olympics to Myanmar, a year through the eyes of Nikkei Asia’s cover story writers

The Myanmar crisis (Feb. 3, April 14 and Sept. 15)

The Big Story ran a series of three articles covering the 2021 Myanmar military takeover.