Myanmar, a violent tale of two governments

A failed state plunges toward civil war{1st Photo Caption: A flash protest in Yangon on May 2. Opposition to Myanmar’s military government continues to swell. (Photo by Berry)}

The Big Story

Myanmar, a violent tale of two governments

A failed state plunges toward civil war

GWEN ROBINSON, Nikkei Asia editor-at-large, and RORY WALLACE, Contributing writer

September 15, 2021 06:00 JST

BANGKOK/YANGON — A video of a little-known political leader declaring war on Myanmar’s military regime went viral on social media on Sept. 7, garnering more than 1 million views on Facebook, Twitter and other platforms within days. Clad in a traditional red-and-purple headdress and white jacket, Duwa Lashi La, an ethnic Kachin lawyer and acting president of the underground National Unity Government, declared a “people’s defensive war” on the military rulers that seized power on Feb. 1.

“We have to initiate a nationwide uprising in every village, town and city in the entire country,” he said, urging civil servants to abandon their posts and ethnic armed groups as well as pro-NUG fighters, known as the People’s Defense Force, to target the military regime’s assets and security forces. “As this is a public revolution, we urge all citizens within the whole of Myanmar to revolt against the rule of the military terrorists led by [Commander in Chief] Min Aung Hlaing.”

The declaration completed the dramatic transformation of a movement that emerged more than three decades ago in the turbulent days of Myanmar’s 1988 uprising, when several thousand people were killed by security forces under Gen. Ne Win’s junta.

It also marked a turning point in the role of Aung San Suu Kyi, head of the National League for Democracy and the country’s de facto leader. She has remained in detention in the capital, Naypyitaw, since her arrest on Feb. 1, glimpsed in occasional photographs of closed hearings in trials she is facing for multiple charges ranging from violations of COVID-19 restrictions to possessing illegal walkie-talkies. A Nobel laureate, she made nonviolent activism a central platform of her pro-democracy movement, spending more than 15 years under house arrest in her struggle against Myanmar’s military regime. Yet, decades later, international condemnation of her defense of the military’s brutal expulsion of Rohingya Muslims in 2017 barely dented her popularity in Myanmar.

Amid the savage campaign by the regime’s security forces to stamp out even mild forms of dissent, the protest movement has seen a radical shift toward a more militant approach in the NLD and its offshoot, the NUG. Styling itself as an underground, parallel government, the NUG has drawn together figures across the political spectrum, from ousted NLD lawmakers and administration members to leaders of civil society and ethnic minority groups.

Duwa Lashi La, acting president of Myanmar’s National Unity Government, addresses the nation in an online speech on Sept. 7. (Screenshot from NUG Facebook page)

Now 76, Oxford-educated Suu Kyi’s mannered approach to politics and governance seems increasingly distant from the concerns of angry young people who have taken to the streets and are resorting to violent means to push back against the military leaders.

“There are two extremes,” said Min Zin, executive director of the Institute for Strategy and Policy, Myanmar. “Many NLD loyalists claim Aung San Suu Kyi is still the ultimate inspiration and the country’s leader while some younger activists and radicals might suggest she is no longer relevant unless she toes the line of this new revolutionary movement. I doubt both claims. I think she is still relevant domestically and internationally.”

The NUG’s shadow cabinet, scattered across the world, holds virtual meetings and uses social media to reach out to supporters at home and abroad. A trial run for the NUG’s clandestine online lottery, launched in August to support striking civil servants, was a sellout, raising $300,000 in days, and establishing a revenue stream that they estimate will earn about $8.4 million per month.

Protesters hold a banner supporting the National Unity Government in Yangon on July 11. In a short amount of time, the NUG has gained legitimacy and popular support. © AFP/Jiji

Since seizing power and establishing the State Administration Council, the generals have set about unraveling many of the democratic reforms of the past decade and reverted to the inwardly focused, quasi-socialist rhetoric of past juntas.

Meanwhile, the NUG has been trying to gain international recognition as Myanmar’s legitimate government in an effort to turn the regime into a pariah. The effort is coming to a head at the United Nations, with a political showdown looming over competing campaigns for accreditation at the 76th General Assembly session opening Sept. 14 in New York.

The NUG’s declaration of war against Myanmar’s military regime represents a turning point for Aung San Suu Kyi, whose approach to politics and governance seems increasingly distant from the concerns of angry youths. (Photo by Berry)

The quest by the NUG and the military rulers for recognition at the U.N. is symbolically important, “but it’s not make or break for the revolution,” said Richard Horsey, an independent analyst and senior Myanmar adviser at International Crisis Group. “This is also not a question of NUG’s legitimacy; they have legitimacy, but they do not hold territory and do not control the country.”

Blitzkrieg

Myanmar embarked on its current path to civil war at dawn on Feb. 1 in the capital, Naypyitaw. Shortly before the country’s new parliament was to convene for the first time since November’s national elections, the military seized power. In blitzkrieg raids, security forces detained Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint and senior members of the government and ruling NLD.

The military takeover — the generals have banned the words “coup” and “junta,” insisting they acted according to the constitution — ended the relative stability and economic growth that Myanmar enjoyed since its transition to quasi-civilian rule in 2011. Polls promised for 2022 have been rescheduled for 2023, but few believe the generals, who have unleashed a brutal national crackdown on dissent that has killed at least 1,080 civilians and seen more than 8,050 people arrested since Feb. 1.

The battle lines solidified on Feb. 26 in an electrifying moment at the U.N. General Assembly, when Myanmar’s permanent representative Kyaw Moe Tun denounced the military and urged the U.N. to use “any means necessary” to reverse the Feb. 1 military takeover, before flashing a three-fingered salute. The defiant gesture, popularized by protest movements in Hong Kong and Thailand, rapidly became a symbol of Myanmar’s “CDM” or civil disobedience movement.

Even before the military on Feb. 9 began using live ammunition to shoot protesters, anti-regime forces began marshaling resources. On Feb. 5, a handful of ousted NLD lawmakers formed a parliament-in-exile, calling it the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, later publishing a new “federal democracy charter” to replace the military-drafted 2008 constitution. United by the urgency of tackling a common enemy, an improbable coalition of lawmakers, civil society figures, ethnic leaders and other anti-junta representatives buried past differences and on April 16 announced the formation of the National Unity Government, headed by Duwa Lashi La as acting president. Both Aung San Suu Kyi as state counselor and President Win Myint have kept their roles in detention, although privately NUG members say that even after their release, they cannot see future roles for them as leaders.

Of the NUG’s 26 “cabinet members,” 13 belong to ethnic nationalities and eight are women — a direct response to past criticisms of the NLD for downplaying the role of women and minorities. Under Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration, no other women held cabinet positions, and there were few ministers with ethnic backgrounds.

The SAC, in clumsy efforts to appear inclusive, has also tried for its version of diversity, appointing 10 civilians, many from ethnic backgrounds, to the 19-member council.

In a striking departure from previous military regimes, the related SAC management committee – which functions as the cabinet — includes at least two women. The unprecedented participation of civilians in the junta itself highlights a significant break with tradition, and “underlines both the nature of the SAC regime as an anti-NLD project and the determination of Myanmar’s armed forces, to make a success of that project,” said a new report by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

As the regime’s security forces intensify their hunt for dissidents, arrest protesters, kill opponents and curb freedoms, the NUG continues to operate both inside Myanmar and abroad, issuing a stream of statements, channeling funds and humanitarian relief to striking workers and blitzing the media. It has also promised to distribute 6 million COVID-19 vaccine doses, mainly in ethnic-controlled areas.

In a related effort to soften its image and woo international acceptance, the military regime on Aug. 1 announced it had become a “caretaker government” and that Min Aung Hlaing was “caretaker prime minister.” Official communications however still refer to the leader as chairman of the State Administration Council.

“A Facebook account and a kitchen knife”

The NUG’s quest for international legitimacy ultimately depends on the nine-member accreditation committee of the U.N. General Assembly, which will consider the question of who, if anyone, will occupy Myanmar’s seat. Ahead of the session, diplomats suggested that the U.S. and China have struck a deal to defer the decision and to maintain the status quo, leaving the incumbent, Kyaw Moe Tun, in place for now. Each side has claimed functioning “cabinets” and security forces, and each has produced policies spanning economic, diplomatic, public health and security matters. Each also has evoked the “people’s will” and claimed popular support. The SAC occupies the seat of government, having annulled the results of the November election by citing what it says is “evidence” that the NLD committed fraud. It also controls a sprawling security apparatus, including more than 350,000 military troops and police.

The NUG says it has the mandate of the legitimately elected NLD and the loyalty of a vast network of striking civil servants. It also claims a trained “people’s defense” force of at least 8,000 members with countless more volunteers forces.

People’s Defense Force troops attend a training ceremony. The force is one of the hundreds of units that continue to crop up across Myanmar. (Screenshot by CRPH Facebook page)

The David-and-Goliath comparisons are obvious. The military regime draws on a $21 billion-plus national budget, with defense spending that exceeded $2.5 billion in 2020 and is likely to grow. Meanwhile, the PDFs — every week several more of these forces appear — are primarily self-funded volunteers. For those under the NUG umbrella, funding lines are unclear. NUG organizers, mindful of the NLD’s earlier declared commitment to “nonviolent means,” say only that the body is assisting in the training and development of a “federal army.”

Many of the PDFs comprise urban youths, hastily trained in hidden jungle camps by ethnic armed organizations. Those who lack firearms and military training aim to target state-linked facilities and pro-regime officials with explosives, sabotage or slingshots. Other groups, particularly in rural areas such as Myanmar’s rugged central region, comprise farmers and hunters armed with shotguns and bows and arrows.

This is fueling a lethal dynamic. Experts who have closely tracked escalating attacks on military and state facilities and personnel across the country estimate the PDFs now range from 120 units to more than 300, with 20,000 to 30,000 members.

With names such as “Thunderstorms Without Borders” and “Kind-Hearted Bone-Heads,” they were initially viewed as brave though often ineffectual amateurs. One military analyst described some PDFs as “little more than a bunch of young friends with a Facebook account and a kitchen knife.” But violent incidents — including direct clashes between PDFs and security forces, assassinations of government officials and explosions — have soared, currently averaging six to 10 per day according to analysts who closely monitor the security situation. The SAC says 850 people have been killed by NUG-connected “terrorists” since Feb. 1. The NUG claims at least 1,300 casualties on the military side and the defection of at least 1,500 soldiers and police to the anti-regime movement. The casualties on both sides could be far higher, military experts say.

“It is impossible to verify numbers, but we know many [ethnic armed organizations] have trained thousands of new anti-coup fighters,” said Min Zaw Oo, executive director of Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security, a Yangon-based think tank. “We have seen at least 344 new, localized armed groups announced on social media.” Actual casualties on both sides are hard to determine, he noted.

Supplementing the regime’s security forces recently have been the pro-regime Pyu Saw Htee militia, hastily trained and armed by state forces. According to Anthony Davis, an independent security analyst, they could easily number 15,000 men, loosely supervised by the military.

Almost inevitably, the proliferation of Pyu Saw Htee units to counter PDF activity has led to a sharp rise in targeted killings of its members and their families along with members of the pro-Min Aung Hlaing Union Solidarity and Development Party and civil administration officials, noted Davis. “Militia groups have responded in kind with threats of retaliatory killings of NLD members and in some cases acted on them.”

The increase in anonymous armed violence involving civilians comes against the backdrop of a collapse in civil administration and a growing vacuum of governance, with the growing view that the military has forfeited any claim to political legitimacy. “Viewed from a national perspective, much of central Myanmar is thereby sinking into a state of violent anarchy,” Davis said.

“Napoleonic tendencies”

With the economy in free fall due to the pandemic, civil unrest and an initial post-takeover paralysis of business, the SAC continues to portray itself as a responsible pro-business manager, trumpeting a string of megaprojects since February, including a $2.5 billion power plant project in Myanmar’s southwest.

In addition to its hold on a vast bureaucracy and state resources, the military-regime’s key advantages are its substantial budget and control of the security forces.

The NUG can claim many advantages, having attracted talent from the bureaucracy and institutions, international goodwill and a vast domestic support base, which is evident in continuing anti-regime protests and the eager purchases of lottery tickets, sold clandestinely over the internet.

Crucially, the NUG and its related National Unity Consultative Council, set up as a diverse oversight body to interface with ethnic and minority groups, have become magnets for disaffected groups across the political spectrum, including in recent months Rohingya minority Muslims, who were initially excluded.

While this is an advantage, the NUG’s purported “unity” has also exacerbated internal differences and led to delays of key initiatives, including a long-promised budget.

Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing ousted Myanmar’s elected government on Feb. 1. © Reuters

In operating styles, the two sides could not be more different. The SAC in true martial tradition follows a strict hierarchy with Min Aung Hlaing at the helm of both the council and the SAC management committee, or cabinet. Meetings typically are dominated by the chief’s pronouncements on everything from economic policy to moral values.

While the regime’s structure reveals “Napoleonic tendencies” as described by a Yangon-based diplomat, the NUG is often hampered by a flat management structure and a critical need for secrecy, with half its members in hiding and operating clandestinely over the internet. The top ministers seem to have abundant leeway in their respective areas, which has led to fraught negotiations over budget priorities. The NUG is proposing a maiden budget of $700 million mainly to support emergency humanitarian relief and an estimated 250,000 striking civil servants. But the amount could top $1 billion in light of the push to support a “people’s war.”

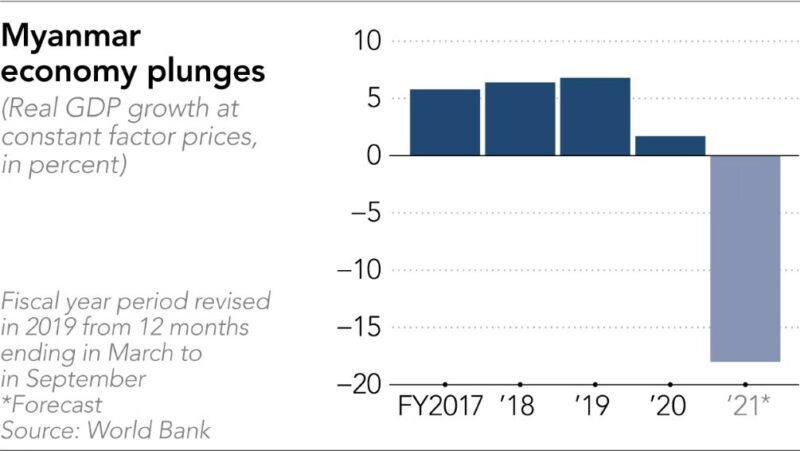

On economic policy, the SAC, borrowing heavily on the reformist playbook of the NLD, has drawn up a Myanmar Economic Recovery Plan, and has tried to engage various potential investors. The military government certainly needs help. The World Bank in July predicted the economy could contract by 18% this year, while private economists believe it could shrink by 25% or more. Amid heavy-handed controls on access to cash and new restrictions on foreign currency accounts, trade has plunged. Inflation is rising, with estimates ranging from the World Bank’s 6% to more than 30% in some areas, according to independent economists. This has triggered a precipitous decline of the local currency, the kyat, which by Sept. 1 had plunged by more than 23% against the dollar since the takeover amid surging black market rates.

Min Aung Hlaing has separately set some national goals that one private economist described as “fantastical,” including plans to build electric vehicles, even though Myanmar has yet to produce even a small petrol-fueled car. He has launched a self-sufficiency drive, banning imports of items such as soap and toothpaste, as well as exhorting farmers to grow more bananas and palm oil.

The draft Myanmar Economic Recovery Plan, not made public but seen by Nikkei Asia, reflects the military rulers’ concerns over a growing liquidity crisis, mirrored in severe limits on ATM withdrawals. It lowers the minimum reserve requirements of banks by at least 1.5% from an earlier 5%.

Telenor has announced the sale of its Myanmar telco to a Lebanese company, but the sale requires military approval. © EPA/Jiji

There has already been a steady exodus of foreign companies and executives from Myanmar. The most prominent has been Telenor, the Norwegian telecom operator, which announced the sale of its mobile operations in the country to Lebanese company M1 Group. Kirin Holdings, the Japanese brewer, said after the military takeover that it would exit its beer-making joint venture with Myanmar’s military but is yet to find a buyer for its stake. Telenor’s sale, meanwhile, still requires the regime’s approval.

“Many businesses operating in Myanmar want stability, but not a coerced form of ‘stability’ forced on the population by way of repression,” said a Japanese investor based in Yangon. An estimated 90% of about 4,000 Japanese expatriates in Myanmar left the country as a result of the pandemic and the overthrow of government. Some have trickled back, although the deepening economic crisis has deterred many expat business people, according to several foreign chambers of commerce.

“Investors who side with SAC and proceed with new investments will face the ire of not only NUG but also of the Myanmar public opinion, with associated reputational risks of naming and shaming, and potentially sanction risks too,” said Romain Caillaud, principal of Tokyo-based corporate advisory firm SIPA Partners and associate fellow in Myanmar studies at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

“But for investors already in Myanmar, the reality is they must engage to some extent with the state apparatus controlled by the SAC, for operational matters such as renewing permits or visas, importing products, or paying taxes,” he added.

Backroom maneuvering

Most foreign governments have failed to take meaningful action over the military’s power grab and subsequent atrocities. Despite some very focused sanctions and strong words, including an unprecedented joint statement by the military chiefs of Japan, South Korea and 10 other countries condemning the regime for atrocities against civilians, Myanmar-related diplomacy has sunk into a diplomatic gray zone.

The U.K. recently sent a new ambassador and nearly all Western missions remain open in Myanmar. However, Australia, France, the Czech Republic and also the U.K. have acknowledged the NUG’s in-country representatives, and the U.S., South Korea and Japan are pursuing quiet contacts with the NUG, Zin Mar Aung, NUG’s foreign minister, told Nikkei Asia.

China, while publicly siding with the military rulers, has shown its well-known tendency to bet on different horses. It has shored up its long relationship with ethnic armed groups operating near its border as well as signaling its desire to maintain links to the ousted NLD. In what some anti-government forces portray as a diplomatic triumph, on Sept. 9 the Chinese Communist Party invited the NLD, alongside pro-regime political parties, to join a meeting of regional political parties.

Myanmar’s military enjoys enormous advantages in funding, equipment and preparedness over the ragtag forces that are cropping up to fight back. © Reuters

China is among the few countries to embrace Min Aung Hlaing’s “caretaker” government. The provincial government in neighboring Yunnan Province and many Chinese governmental and quasi-governmental agencies have established or resumed working-level ties, dramatically scaling up cross-border aid — particularly to help curb COVID-19 — through the SAC. But Beijing has also signaled concerns about the military’s attempts to dissolve the NLD, say diplomats familiar with the move.

“Since July, China has sent what might be read as a series of mixed signals over how it sees the SAC and the NLD/NUG,” said Jason Tower, Myanmar country director of the United States Institute of Peace. “The bottom line is that China is worried about stability in Myanmar, which could be caused by either the dissolution of the NLD or increased military actions by the NUG. Beijing has placed pressure on both the Myanmar military and [the ethnic armed organizations] to declare cease-fires. The aim is to ensure the security of Chinese assets and nationals there.”

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, traditionally reluctant to involve itself in the “internal affairs” of member countries, has taken a more ambivalent approach toward Myanmar.

An April summit in Jakarta produced a five-point “consensus plan” that includes calls for cessation of violence and emergency humanitarian relief, as well as an agreement to appoint a special envoy. It took many months of backroom maneuvering to agree on what many see as the “compromise candidate” — Erywan Yusof, Brunei’s second foreign minister.

Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, bottom right, gains some international legitimacy by meeting with ASEAN leaders in Jakarta on April 24. © Indonesian Presidential Palace/AP

The lack of international action has driven the new militancy among anti-regime forces. Privately some Western diplomats expressed concern about the NUG’s declaration of war. “While understandable, it really complicates matters, particularly for outreach to the opposition,” noted a Bangkok-based Western diplomat. The U.S. and the U.K. say the conflict should be resolved through dialogue and that both sides should avoid an escalation of violence.

In some respects, the NUG’s declaration of war has resounded most loudly in Beijing, which is worried about a failed state on its doorstep. China’s recent efforts to directly shore up ties with the NLD reflect calculations about how its decline is impacting stability in Myanmar, Tower said. “For these same reasons, China is much more cautious about the NUG, which it increasingly identifies as a source of instability,” he said.

China had pressured the ethnic armed organizations operating near its border to announce ceasefires with the military, while “Chinese interactions with the NUG and NLD are likely to continue to focus on encouraging restraint and on ensuring the security of Chinese assets and nationals in the country,” Tower said.

Tower also believes China will continue to offer political support to the military regime as well as weaken norms on international interventions in support of human rights and democracy. “China will clearly take all this into consideration as it approaches discussions at the General Assembly,” he said.

Turning the screws

Perhaps more important than what happens at the U.N. is whether Myanmar will face increased international sanctions. Some Western governments had sanctioned key military figures and interests before the takeover in response to the brutal expulsion of Rohingya Muslims in 2017. More sanctions, led by the U.S., U.K. and EU, have been added since. They target not only military figures but civilian technocrats serving in the SAC government, such as investment minister Aung Naing Oo, and two main military conglomerates, Myanmar Economic Corp. and Myanma Economic Holdings.

But critics say the sanctions will be ineffective as long as Western governments fail to target Myanmar’s offshore oil and gas sector. The government’s biggest earner of hard currency in 2020 produced $3.3 billion in revenue, according to U.N. data. Key investors in the sector include French energy giant Total, Chevron of the U.S., Thailand’s PTT Exploration & Production and South Korean operator Posco International. Total and Chevron in May suspended dividend payments on one state-linked pipeline business in Myanmar, but this accounted for a tiny fraction of the regime’s gas revenue.

State-controlled gem, timber and pearl businesses have also been sanctioned, but broad sanctions that were imposed on Myanmar’s previous military governments have not been reinstated.

Myanmar’s future will likely depend on which government, the SAC or NUG, gains greater international acceptance.

“The SAC is clearly more cohesive and coherent,” Caillaud of Tokyo-based advisory SIPA Partners said, “while the NUG’s aim to represent Myanmar’s political and ethnic diversity means its policies and actions [are sometimes] confusing if not conflicting. Still what NUG has gained that SAC lacks is legitimacy and popular support both domestically and internationally.”

Additional reporting by Nikkei staff writers.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Myanmar: Inside the coup that toppled Aung San Suu Kyi’s government – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Myanmar: Inside the coup that toppled Aung San Suu Kyi’s government

Failed state: Myanmar collapses into chaos – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Failed state: Myanmar collapses into chaos

A divided international response, a fractured country and a murderous regime

The Myanmar crisis – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Coups, couriers and COVID: The Big Story 2021 Hall of Fame

From the Tokyo Olympics to Myanmar, a year through the eyes of Nikkei Asia’s cover story writers

The Myanmar crisis (Feb. 3, April 14 and Sept. 15)

The Big Story ran a series of three articles covering the 2021 Myanmar military takeover.