Failed state: Myanmar collapses into chaos

A divided international response, a fractured country and a murderous regime{1st Photo Caption: By one count, over 700 citizens have been killed in Myanmar since the Feb. 1 coup. But the international community remains paralyzed, even as the cycle of protests and bloody crackdowns continues. © Photo by Getty Images}

The Big Story

Failed state: Myanmar collapses into chaos

A divided international response, a fractured country and a murderous regime

DOMINIC FAULDER, GWEN ROBINSON and MARWAAN MACAN-MARKAR, Nikkei staff writers

April 14, 2021 06:01 JST

BANGKOK/YANGON — At 5 a.m. on Friday, April 9, in Bago, one of Myanmar’s ancient capitals, heavily armed troops mounted an assault on demonstrators barricaded in along Ma Ga Dit and San Taw Din roads on the east side of town.

The shooting finally paused around 10 p.m. with at least 83 people dead, said local news organization Myanmar Now. Troops had reportedly dragged 57 bodies into the Zeyar Muni pagoda compound and a school, ignoring exhortations from monks to provide medical attention to the wounded. Some, seriously wounded but still alive, could be heard moaning among the corpses.

The same morning, a military tribunal in Yangon sentenced 19 people to death for killing a single soldier — 17 in absentia.

Bago — or Pegu, as it was known during its time as a royal capital — has become one of the most blood-drenched places in Myanmar, a tormented land that has been sliding into an abyss since Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing staged a coup on Feb. 1.

A protester screams at passing police vans in Yangon, Myanmar. (Photo by stringer)

Troops have been filmed shooting randomly into houses, at least 46 children have died, and more than 3,000 activists and civil society leaders have been detained. By Monday, over 700 people in total had been killed around the country by armed troops and police, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners. The regime’s tally on Friday was 248.

“Everybody is going into the streets because we are on the edge and about to fall, so we need to save ourselves,” said Thinzar Shulei Yi, a Burmese activist currently in hiding, to digital news group New Naratif. “The people have realized that we are our only saviors.”

Many experts see the country in a deadly spiral. They voice fears of another Syria — even though no other countries are so far involved in the country’s implosion.

“Myanmar stands at the brink of state failure, of state collapse,” Richard Horsey, International Crisis Group’s senior adviser for Myanmar, briefed the U.N. Security Council on April 9. “The actions of the regime are not just morally reprehensible. They are also extremely dangerous.”

Governed mostly by the military since 1958, Myanmar has not witnessed such violence since August and September of 1988, when the military put down a pro-democracy uprising. It left an estimated 3,000 dead in six weeks and 500 more in the final coup of Sept. 18.

This time, the civil uprising has been more sophisticated and resilient. But the international community has remained paralyzed as the cycle of protests and bloody crackdowns continues with no end in sight.

“Not only has the military been unable to consolidate its attempted coup and effectively govern the country, but also its actions may be creating a situation where the country becomes ungovernable,” said Horsey.

Terror and dishonor

The bloodiest day so far was March 27, when Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, celebrates Armed Forces Day, originally held to mark the start of Burmese resistance to Japanese occupation in World War II.

As usual, garlanded troops marched around a massive parade ground in Naypyitaw, the new capital, watched over by giant effigies of ancient Burmese kings. Elsewhere that day, their comrades and police gunned down an estimated 114 citizens.

“A day of terror and dishonor,” the European Union delegation to Myanmar said of the violence.

The coup ended a five-year experiment with limited democracy. An election in 2015 was won in a landslide by the National League for Democracy led by Aung San Suu Kyi, who, as state counselor, became the country’s de facto leader the following year, as well as foreign minister. The military retained three key ministries and a 25% bloc in parliament to veto any constitutional changes. Apart from the tentative steps toward democracy, many fear the coup has also wiped away considerable economic advances made over the past decade.

Myanmar’s junta chief, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, presides over an Armed Forces Day parade in the capital of Naypyitaw on March 27. © Reuters

Min Aung Hlaing was evidently disconcerted by the increased popularity of the NLD, particularly as it blocked any chance of him assuming the presidency after his mandatory retirement due in July. Claiming fraud in the election, he sprung his coup using a mechanism built into the military’s 2008 constitution. Suu Kyi remains under arrest and facing trial on trumped-up charges ranging from corruption to illegal ownership of walkie-talkies.

A resilient civil disobedience movement has emerged, as has an alternate government in hiding — the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), made up mostly of elected NLD politicians.

The junta has used ruthless methods against its opponents. On April 5, six family members of an NLD official in hiding were taken hostage. They included his daughter and nephew, aged 4 and 2.

“The junta will use any means available to consolidate power,” Nay Yan Oo, a Yangon-based political analyst, told Nikkei Asia.

The international community has reacted predictably: sternly condemning the Tatmadaw but so far failing to prevent the situation from deteriorating. The administration of President Joe Biden has said it wants to reassert the U.S.’s moral authority as leader of the free world, but it is not about to enter China’s backyard.

“The U.S. will be trying to forge a multilateral approach to Myanmar — but fears of an American invasion are completely misplaced,” Jonah Blank, a senior political scientist at Rand Corp. and former policy director for South and Southeast Asia on the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, told Nikkei.

Sam Zarifi, secretary-general of the International Commission of Jurists, told Nikkei that meaningful action by the United Nations Security Council was extremely unlikely due to Russian and Chinese vetoes. Meanwhile, although Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore have individually made clear their deep concerns about Myanmar, the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations is constrained by a code of mutual noninterference that inhibits any meaningful response.

The U.S. and EU have so far imposed sanctions on individuals and groups linked to the coup, including two conglomerates controlled by the military, and have suspended all trade deals. The U.S. government blocked the Myanmar central bank’s attempt in early February to transfer $1 billion at the Federal Reserve Bank in New York.

The U.S. State Department has said it is “appalled” by the violence against protesters, which it termed “immoral and indefensible.”

Protesters with slingshots take cover behind a barricade in Monywa, in the Sagaing region of Myanmar, on March 29. © Reuters

The Tatmadaw has never been afraid of international isolation, however. Burma, as the country was previously known, refused to join the British Commonwealth and even dropped out of the Non-Aligned Movement. The military has long seen its mission as ensuring ethnic Burman supremacy and forging national unity. Nicholas Coppel, the former Australian ambassador to Myanmar, described it to Nikkei as “a flawed culture of exceptionalism, otherness and unaccountability.”

“This is the only army on planet Earth which for seven decades has never stopped fighting,” Anthony Davis, a Bangkok-based defense analyst, told Nikkei. “That does something to men’s heads, and at the rank-and-file level what it does is it brutalizes.”

Davis picked out Myanmar, Pakistan and Thailand as countries controlled by their militaries — Myanmar being the most extreme of the three. “You have an army which sees itself not just as an armed force that defends the nation’s borders, but rather as the embodiment of the soul of that country.”

“This is the only army on planet Earth which for seven decades had never stopped fighting. That does something to men’s heads”

Bangkok-based defense analyst Anthony Davis

“The Tatmadaw is a unique example of extreme nationalism which has been honed by decades of blood and paranoia,” said Davis. He described the Burman-dominated officer corps as a “caste” or “elite within an elite,” since Burmans account for some 70% of the population.

Davis observed that some countries in the region see the Tatmadaw as holding together a country that could otherwise become a second Afghanistan — a failed state within mainland Southeast Asia. Others, however, see the Tatmadaw as a brainwashed armed cult, its unremitting tyranny over ethnic minorities shattering any hope of genuine national unity.

The Tatmadaw has been ruthless in its efforts to restart the economy, so far without success. Supermarket and bank employees have been rounded up and forced back to work. A Thai investor who has already laid off hundreds of Burmese despaired after being instructed by the military to order his people back.

“If we don’t comply, we will likely be fined,” he said. “If we do, they run the risk of having their brains blown out.”

In Yangon, a young woman working for South Korea’s Shinhan Bank was fatally wounded by soldiers as she went home in a corporate van.

Armed Forces Day in Naypyitaw: The military has long seen its mission as ensuring ethnic Burman supremacy and forging national unity. © Reuters

The Myanmar Center for Responsible Business organized 68 foreign companies and 164 locally registered companies to sign a collective statement of “growing and deep concern.” They called for respect of human rights and a return to democracy and the rule of law.

The Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Myanmar has raised concerns over the violence and called for recovery “under democracy.” By March’s end, all foreign chambers of commerce representing Western businesses had publicly condemned the atrocities, repeating their calls for unrestricted information access and the free flow of information — but to no effect.

“Under these circumstances, no Japanese companies are able to progress their business,” said Shinsuke Goto, CEO of financial advisory Trust Venture Partners. “Most of them are just concentrating on how to maintain employment despite the uncertainty ahead.”

Despite dwindling revenues, the junta has an iron grip on the country’s lucrative gas production. Total, the French operator of the Yadana gas field, is continuing production and paying taxes, despite calls from the CRPH and others to cut the junta off. CEO Patrick Pouyanne wrote in Le Journal du Dimanche newspaper that the company must maintain electricity supplies — and also protect staff from forced labor. Total had considered putting $4 million it owes in taxes into an escrow account, but Pouyanne said that would expose local managers to imprisonment. He has instead said that the company will contribute the equivalent of its Myanmar taxes toward promoting human rights in the country.

What is a failed state? “Nation-states fail because they are convulsed by internal violence and can no longer deliver positive political goods to their inhabitants. … Their governments lose legitimacy”

Robert I. Rotberg, former president of the World Peace Foundation

Ethnic minorities protest in Yangon. (Photo by stringer)

Offshore gas sales are a crucial source of foreign exchange. The export of “petroleum gases and other gaseous hydrocarbons,” including natural gas, was worth $3.3 billion in 2020 — about 20% of Myanmar’s exports. Thailand accounts for $1.8 billion, and China for $1.5 billion.

The defense budget was $3 billion in 2020, but the Tatmadaw also owns two major conglomerates: Myanma Economic Holdings Ltd. and Myanmar Economic Corporation. MEHL was Myanmar’s second-biggest income tax payer in the 2018-19 fiscal year, with subsidiary Myawaddy Bank the fifth.

Pariah state

The Tatmadaw had hoped to have the post-coup situation in hand by March 27, and sparse attendance at Armed Forces Day was a barometer of international antipathy toward the junta. Only eight countries were represented: Russia, Bangladesh, China, India, Laos, Pakistan, Thailand and Vietnam. Western military attaches stayed away — as did South Korea’s and Japan’s.

The Tatmadaw, however, continues to spend big on weaponry — willingly supplied by key friends. India supplies some arms, and the two countries share a 1,500 km border. Bangladesh, China, Laos and Thailand also share difficult frontiers with Myanmar.

In the evening, senior officers and their wives attended the Armed Forces Day grand reception held on the lawns of Zeyathiri Villa in the capital, with fireworks before dinner. Russia’s deputy defense minister, Gen. Alexander Fomin, was present as an honored guest. In a speech to the crowd, Min Aung Hlaing praised the Russians “for their substantial support to the Tatmadaw … though we are far apart.”

That crucial physical distance makes Russia nonthreatening, and relations have blossomed on Min Aung Hlaing’s watch. He has visited the country at least six times since becoming senior general in 2011, part of his bid to create a modern “standard army” that would replace a force based on light infantry while focusing on counterinsurgency.

Fomin’s boss, Defense Minister Gen. Sergei Shoigu, was actually in Naypyitaw in the weeks before the coup, signing an arms deal, but what advice he might have offered is unknown. A Russian foreign ministry spokesperson this month said sanctions would only hurt ordinary people and could lead to civil war.

Many of the armored personnel carriers deployed since the coup are Russian. Over the decade to 2019, Myanmar had paid an estimated $807 million for Russian hardware, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, which tracks arms trading. The Tatmadaw has acquired MiG-29 jets, Yak-130 jet trainers, Mi-24 and Mi-35P helicopters, and Pechora-2M anti-aircraft missile systems. More sophisticated materiel is in the pipeline, including Orlan-10E surveillance drones.

Russia’s interest in Myanmar focuses on arms sales, said Alexander Gabuev of the Carnegie Moscow Center, a Moscow-based think tank, adding that the Kremlin also had good relations with the previous civilian government. Its support of the junta has so far been “symbolic” and limited to diplomatic support, including at the U.N., he said.

However, “there is an opportunity to signal to the West that Russia is a risk-taking and aggressive player on the global scene that doesn’t care that much about U.S. and EU objections when making a move,” he said.

Over 6,000 Tatmadaw officers have received science and engineering degrees in Russia. The growing ties with Russia have reduced Myanmar’s dependence on arms from China, although it still supplies half the total. There have been quality issues as well as disquiet over China arming some ethnic armed organizations, including the Kachin and the Wa.

Karen refugees carry their belongings along the Salween riverbank in Mae Hong Son, Thailand, on March 29. © Karen Women’s Organization/Reuters

“China maintains strong relations with the EAOs based along Myanmar’s northern border, including armed groups that are actively fighting the Tatmadaw, militias that side with the coup-makers like the Kokang Border Guard Forces, as well as the EAOs that have not taken a position on the military’s power grab,” Jason Tower of the United States Institute of Peace told Nikkei.

The largest EAO is the United Wa State Army, which has Chinese support but also strong business links to the Tatmadaw. Another significant force, the Restoration Council of Shan State under Gen. Yawd Serk, has condemned the coup but done nothing more. The Karen National Union, ranged along the Thai border, and Kachin Independence Army on the Chinese border have stepped up hostilities, taking territory and outposts.

The KNU overran a Tatmadaw outpost during the Armed Forces Day parade, reportedly killing 10 soldiers. Jets bombed the area at 8 p.m. as the reception was underway in Naypyitaw. Thousands of Karen have been displaced near the Thai border. The KIA, meanwhile, overran an outpost in late March near the China border. Tower expects other EAOs to engage, stretching the Tatmadaw on more fronts.

Saturday saw a rare EAO joint operation that might hint at greater cooperation to come. A police station in Shan state was overrun by rebels from the Arakan Army, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance. Fourteen police officers were killed.

Min Aung Hlaing has been described as imperious, impetuous and not overly bright. But after 10 years, any potential rivals are gone. Younger, better-informed officers who may have sat in the military’s parliamentary bloc are not in senior command positions. He has not named a successor, though, which some experts say might betray insecurity over allegiances once he retires.

One of the first things the senior general did after seizing power was to send a letter to Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha in Thailand, explaining his coup and asking for help to support democracy. Prayuth revealed the letter’s existence during a news conference.

“We adhere to the important ASEAN principle of noninterference, but of course we are following closely the situation with our neighbor,” Prayuth told Nikkei on April 9. “Thailand and ASEAN hope that violent incidents may end from all sides and that there is a peaceful resolution as soon as possible.

“We have a border of over 2,400 km, and naturally there are concerns about refugee influxes, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. We are already providing humanitarian assistance and have long experience with it. Our goal will always be to see peace and regional harmony in ASEAN.”

With Myanmar’s increasingly bloody implosion in its third month, Prayuth is the only foreign leader Min Aung Hlaing has publicly reached out to. “They don’t want to depend only on China, and Russia is a bit far away,” a retired Thai diplomat long familiar with Myanmar told Nikkei. “Thailand is the back door, and they need it to be open.”

Protesters hold posters of the detained Aung San Suu Kyi during a rally in Yangon. (Photo by stringer)

Min Aung Hlaing’s letter was not entirely surprising. Well before Prayuth returned as prime minister following an election in 2019 conducted under a military-drafted constitution, the senior general received a Thai military delegation in Naypyitaw. His relations with Suu Kyi had frosted over in 2017 and deteriorated to virtually nonexistent thereafter. A Thai officer asked Min Aung Hlaing about the possibility of a coup.

“I will only stage a coup d’etat if Gen. Prayuth is prime minister in Thailand,” the senior general answered.

“The Thai factor is important, but the question is whether we want to move or not,” the retired diplomat told Nikkei. “Will any of these people feel revulsion to the pictures of women and kids being shot, or just say it is karma?”

He also acknowledged that finding a suitable Thai emissary would be challenging: “It is almost like asking if there is anyone who can be prime minister apart from Prayuth at the present time.”

Thailand experienced massive refugee influxes from Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in the wake of wars in Indochina. It is also home to over a million vulnerable Burmese workers, the largest concentration abroad.

“The Tatmadaw’s killing rate has been particularly high,” said Zarifi of the ICJ. “They reached the sad milestone of 500 deaths faster even than [Syrian President Bashar] Assad did at the onset of the uprising in Syria.” The comparison is ominous, because Syria has since generated 6.6 million refugees, the highest number in the world.

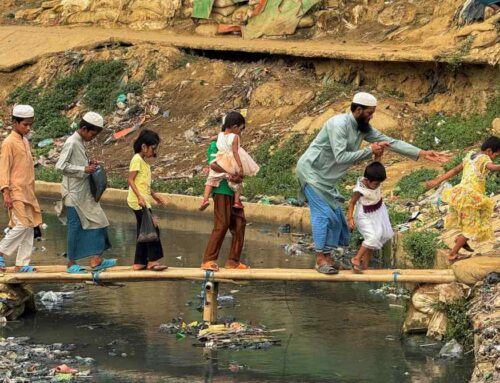

Before the coup, Myanmar was already the fifth-largest source of refugees globally, with over a million listed by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees in January among 1.9 million Burmese “persons of concern.” Most are Rohingya, a persecuted Muslim minority. There are 840,000 in Bangladesh, most of whom arrived in 2017 after a brutal counterinsurgency sweep by the Tatmadaw. With the man in charge of that operation now ruling the country, even the very poor repatriation prospects they entertained previously have vanished.

An estimated 600,000 Rohingya remain in Rakhine state, 142,000 of whom are internally displaced. There are another 153,000 Rohingya in Malaysia. Thailand, meanwhile, has at least 93,000 refugees from other ethnic minorities. That long-standing population had been steadily diminishing in recent years but is now expected to rise again.

‘The clock is ticking’

International options are limited. “It’s hard to see the U.N., ASEAN or Asia generally, given its strategic rivalries, realistically being able to prevent the catastrophe unfolding in front of our eyes,” author and historian Thant Myint-U told Nikkei. “But that only means we have to try harder to find one. The clock is ticking.”

Analysts think some countries will indict top Tatmadaw figures using universal jurisdiction, which enables national courts to prosecute violations of international law, such as crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide. Zarifi told Nikkei that efforts to impose targeted sanctions will expand, noting that Myanmar’s military elite and cronies generally bank abroad in Singapore and Hong Kong.

“I expect there will be efforts to freeze their accounts, and those of their businesses, under sanctions but also under existing trafficking and money laundering laws, all of which have real teeth,” he said.

“Evidence must be collected before it is lost or destroyed,” Kingsley Abbott, the International Commission of Jurists’ director for global accountability and international justice, told Nikkei. “There needs to be regional and international support for the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar created in 2018 by the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva. It has the mandate to gather evidence of violations since 2011.”

He said a venue for prosecutions must then be identified in states willing to exercise universal jurisdiction or before the International Criminal Court. The latter would, however, require a referral by the U.N. Security Council.

Deputy Foreign Minister Kyaw Myo Htut has already fired back at the HRC, flatly rejecting “any measure which could lead Myanmar to international judicial system and any judgement that could erode the ongoing domestic judicial mechanisms.”

“Our position is utterly clear relating to ICC as it shall not exercise the jurisdiction over Myanmar, a nonstate party to Rome Statute,” he said.

“International avenues for justice are only necessary because Myanmar is currently unwilling and unable to deliver accountability itself,” said Abbott.

Additional reporting by Nikkei Asia contributing writer Rory Wallace in Yangon and a Nikkei staff writer.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

Related Articles:

Myanmar: Inside the coup that toppled Aung San Suu Kyi’s government – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Myanmar: Inside the coup that toppled Aung San Suu Kyi’s government

Myanmar, a violent tale of two governments – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Myanmar, a violent tale of two governments

A failed state plunges toward civil war

The Myanmar crisis – NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW

The Big Story

Coups, couriers and COVID: The Big Story 2021 Hall of Fame

From the Tokyo Olympics to Myanmar, a year through the eyes of Nikkei Asia’s cover story writers

The Myanmar crisis (Feb. 3, April 14 and Sept. 15)

The Big Story ran a series of three articles covering the 2021 Myanmar military takeover.