Coronavirus pushes 38m Asians below poverty line: World Bank

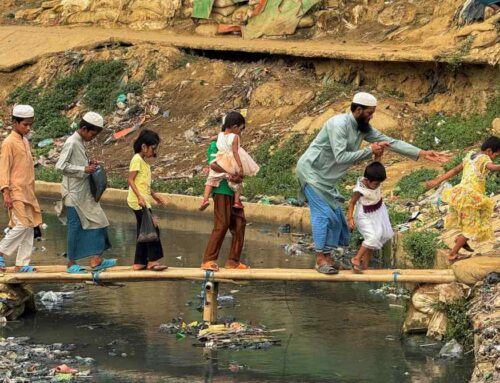

Tourism collapse and weak exports fuel rise of ‘new COVID poor’{1st Photo Caption: A Filipino family eats instant noodles, in a tent set up as a makeshift evacuation center, amid the coronavirus outbreak, in Manila. © Reuters}

ECONOMY

Coronavirus pushes 38m Asians below poverty line: World Bank

Tourism collapse and weak exports fuel rise of ‘new COVID poor’

GWEN ROBINSON, Nikkei Asian Review editor-at-large

September 29, 2020 11:08 JST

BANGKOK — The East Asia and Pacific region faces a rapidly growing class of “new COVID poor” despite relative success in containing the pandemic, according to the World Bank.

Strict lockdown measures and external factors including the collapse of tourism and weak demand for the region’s exports are sinking 38 million people below the poverty line of $5.50 a day and driving a 3.5% contraction in 2020 throughout 13 developing economies.

The hardest-hit economies include those most exposed to tourism and exports. The World Bank’s “low case” scenario estimates an annual fall in gross domestic product for 2020 of up to 10.4% in Thailand, 9.9% for the Philippines and 6.1% in Malaysia — and a 25% plunge for Fiji.

Including China — which has seen a better than expected recovery from the pandemic due to government spending, strong exports and a low rate of new infections — the region is expected to grow 0.9% this year, still the lowest rate since 1967.

But the figure masks the pervasive impact of coronavirus-related poverty across the board, including on the lower middle classes and those in the informal economy.

Adding 38 million “new poor” in the region means 517 million people there now live below the poverty line, an increase of nearly 8% from 2019 and a reversal of the steady improvement in recent decades.

The estimate covers 33 million people who would have escaped poverty had it not been for COVID-19 and another 5 million pushed back into it. But there are many more among the “new COVID poor” who have not been captured by these statistics, said Aaditya Mattoo, the World Bank’s chief economist for East Asia and the Pacific.

“There has been a big hit to earnings all along the income distribution chain,” he told Nikkei Asia. “We are seeing people who were not [classified as] ‘poor’ now jumping to ‘poor.’ They include the lower middle class, people in informal jobs in sectors like tourism — they are not part of the usual poverty registry.”

In its report on the region issued Tuesday, the World Bank highlighted worse than expected consequences from the pandemic, including the “triple shock” syndrome: the pandemic itself, the economic impact of containment measures and reverberations from the global recession.

Another key finding stems from school closures due to COVID-19, which the report estimated could result in a loss of 0.7 learning-adjusted years of schooling throughout the region. As a result, the average student could face a reduction of 4% in expected earnings every year of their working lives, the report warned.

On the economic front, supply and demand shocks — both domestic and foreign — in the first half of 2020 drove the deepest falls in the region’s economic activity in decades, the report said. Regional output contracted by an annual rate of 2.2%, reflecting pandemic-related lockdowns and plunging exports. The impact was uneven, with output contracting by 1.8% in China and by 4% on average in the rest of the region.

In most countries, manufacturing and service employees were hit hardest. Lockdowns and collapsing demand made job losses more prevalent among workers in accommodation and food services, transportation, construction and manufacturing.

These activities tend to have higher informal job rates and little scope to work from home, the report noted.

Mattoo warned that new inequalities were emerging as old ones were being sharpened as a result of COVID-19 and containment measures. One area he emphasized was the need for more government spending on social protection, which since the outbreak earlier this year has averaged to barely 1% of GDP among the developing East Asian countries – the lowest of any region in the world and half the average spent in Europe and Central Asia.

“The rich can telecommute, the poor cannot; the rich can self-isolate, the poor live in slums; children of the rich can do online classes; the rich have savings, the poor do not,” he said.

While the region to date has suffered less from COVID-19 than other parts of the world — even though the disease originated in China — recovery has been mixed.

China is projected to grow by as much as 2% this year, and Vietnam — which was able to control the pandemic at “relatively low human and economic costs” — could grow by 2.8%, despite its high exposure to trade and deep engagement in global value chains.

But Malaysia and Thailand are especially suffering from sharp drops in exports and tourism, and they remain vulnerable to abrupt changes in external financing conditions, the report warned. In addition, both countries are seeing escalating political unrest while neighboring Myanmar, now suffering a second wave of COVID-19 infections, is preparing for elections in November.

Ultimately, the region’s recovery, like in the rest of the world, depends greatly on the timing and availability of a COVID-19 vaccine, Mattoo said.

“The challenge will be to distribute it fairly and efficiently,” he said.

Amid hopes for the arrival of a vaccine in 2021, the World Bank sees brighter prospects for the region next year. It expects growth to reach as much as 7.9% in China, up from 2% in 2020, and 5.1% for the rest of the region, based on the assumption of continued recovery and normalization of activity in major economies.

But regional output is expected to remain well below pre-pandemic projections for the next two years.

In terms of policy options, the World Bank urged the region’s governments to consider seven initiatives.

These include support for companies to prevent bankruptcies and unemployment; fiscal reforms such as widening the tax base to allow more spending on relief measures without sacrificing public investment; and expanding social protection to cover all existing and new poor residents while investing in better infrastructure for delivery of such assistance.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW