Thai protests build as pandemic fuels unrest across Southeast Asia

How COVID aggravated inequality and triggered political reckoning across the region{1st Photo Caption: Thai protesters defiantly throw up a three-finger salute, their demonstrations part of a regional pattern of instability. The World Bank terms it a “third shock,” coming on the heels of both the pandemic and the cost of containing it. © Getty Images}

THE BIG STORY

Thai protests build as pandemic fuels unrest across Southeast Asia

How COVID aggravated inequality and triggered political reckoning across the region

GWEN ROBINSON, Nikkei Asia editor-at-large, MARWAAN MACAN-MARKAR, Asia regional correspondent and SHAUN TURTON, contributing writer

OCTOBER 21, 2020 05:13 JST

BANGKOK/PHNOM PENH — Something changed in the tone of the protests sweeping Thailand when police on Friday turned water cannons on youthful activists in central Bangkok. The confrontation was at a rain-soaked intersection, only meters away from the spot where, a decade earlier, security forces had shot and killed scores of anti-government protesters.

The crowd on this stormy Oct. 16 night represented a new generation of activists taking on the ultimate taboo subject: the immense power and wealth of the Thai monarchy. They are led by students, many of them of high-school age, and tonight they were determined to stand their ground. Ploy, a 19-year-old university student, and her two friends braced themselves as jets of blue-tinged liquid hit the crowd.

“It stung. We knew then that they’d gone too far, that we cannot let them get away with this,” she said.

The protesters, unfazed, formed umbrella chains and flashed three-finger salutes, a symbol of defiance drawn from “The Hunger Games” film series. Some supporters on the overpass above dropped umbrellas to the crowd. The young activists had gathered despite a new emergency decree banning gatherings of five or more people, determined to press their demands for reform and to voice anger at the arrest of more than 20 protest leaders, mostly students, earlier that week.

The demonstrations — calling for the resignation of the prime minister, a new constitution and reform of the monarchy — have steadily intensified, even as the country remains closed to international tourism amid concerns about COVID-19. The latest rallies have drawn tens of thousands of people to locations around the country, as a wave of sympathy grows for the young protesters along with anger at government tactics.

Protests have intensified in Bangkok and elsewhere around the country. “The Thai government has created its own human rights crisis,” said Human Rights Watch. © Getty Images

Immediately after the water cannon attack, three of the top 10 hashtags trending worldwide on social media were about Thailand’s turmoil, many prompted by protesters’ complaints that the water fired from the cannons was laced with stinging chemicals. Swift denials by police failed to stem condemnation from domestic and international critics, including human rights groups and student bodies.

“The Thai government has created its own human rights crisis,” said Human Rights Watch. “Criminalizing peaceful protests and calls for political reform is a hallmark of authoritarian rule.”

An outpouring of international support and sympathy has further energized the young protesters. “Whatever happens next, we’ve already won. We’ve forced the government to take us seriously, we’ve broken the taboo of discussing the monarchy,” said Ploy. “This can’t go away, it can’t go backwards.”

Fresh moves by the government to censor Thai media in recent days have also backfired, fueling further criticism and a growing backlash against the country’s unpopular monarch, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, and Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha. Street graffiti has recently appeared proclaiming the “Republic of Thailand” — unthinkable even six months ago. But today, the authorities seem powerless to counter the anti-monarchy tide.

Thailand has emerged as a “COVID-19 star” in holding down case numbers — but its tourism-reliant economy has also suffered among the worst. (Photo by Lauren DeCicca)

Standing amid the roaring, densely packed protest crowds, it is hard to imagine that just half a year ago, Bangkok’s major thoroughfares were silent and empty amid a deep lockdown, the population more fearful of the COVID-19 pandemic than political repression.

COVID-19 and economic hardships have barely figured in the fiery speeches and social media posts of the Thai protest movement. The main issues are political change, democratization and burning anger at the actions of the politicians and military, and displays of royal wealth that now saturate an emboldened local media. Yet, the catalyst has undoubtedly been the long period of lockdown and antivirus measures, resulting in deepening economic gloom, soaring poverty and a growing sense of hopelessness among the 520,000 students who will graduate from Thai universities in coming weeks. A recent survey showed that as many as 80% of them have no clear idea of the jobs they might land after graduation.

Ironically, the swelling street demonstrations are also the result of one of the government’s signature successes: The young protesters are not afraid of COVID-19. They know that the government has earned international praise for its management of the pandemic. Thailand has been described as one of the world’s “COVID-19 stars,” with less than 60 deaths and barely 3,700 cases as of Oct. 20.

But with its tourism-reliant economy collapsing and economic contraction of more than 10% forecast this year, it has also emerged as one of Asia’s biggest economic losers.

Thailand is a “victim of its own success” in warding off the coronavirus, said the U.S. ambassador to Thailand, Michael DeSombre. Summing up the government’s dilemma, he said the country must find a balance between addressing urgent economic needs and virus prevention.

The economic fallout has highlighted Thailand’s ranking as one of the most unequal countries in the world. According to Credit Suisse’s 2018 “Global Wealth Report,” the richest 1% in Thailand controlled almost 67% of the country’s wealth.

Since 2017, the wealthiest person in Thailand has been the king, who transferred crown property assets into his name following the death of his father King Rama IX a year earlier. Estimates for the vast portfolio of property and shareholdings range from $40 billion to $70 billion. That fact has not been lost on the protesters who are defiantly breaking harsh laws against criticism of the royal family.

As politics, economics and social dislocation converge in the escalating protests, Thailand stands as a cautionary tale for the region despite its outstanding public health record. Just as the country is struggling to restore investor confidence, reopen to tourism, rescue failing businesses and support its swelling population of the poor, doubts are being cast on its stability and security.

Low cases, high cost

Southeast Asian governments have become painfully aware of the trade-offs between fighting the pandemic and shoring up their flailing economies. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 they have experimented with mixed success in re-opening their economies in the absence of an effective vaccine. In Thailand, the closure of borders helped ward off the virus even as it now ravages neighboring Myanmar and prompts fresh lockdowns in the Philippines and Indonesia. But Thailand has paid a high price for its public health success.

Within Southeast Asia, the World Bank’s growth forecasts for individual countries contain some grim “low case” estimates. Thailand is the worst hit economy with an estimated 10.4% contraction, followed by the Philippines (-9.9%) and Malaysia (-6.1%).

Unlike its main trading partners, China, the U.S. and the EU, Southeast Asia’s reliance on external markets has made it more vulnerable to the “triple shock” of COVID-19: the pandemic itself, the economic impact of containment measures and reverberations from the global recession.

Royal Thai Army soldiers move through Bangkok to sanitize the city in March, passing a portrait of the king. (Photo by Akira Kodaka)

The good news for Southeast Asia is that the region has escaped the horrific scale of fatalities and contagion that have befallen the U.S. and parts of Europe, Latin America and South Asia. Within the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations, COVID-19 has caused about 19,000 deaths among the 650 million population, although Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar are all experiencing spiraling “second wave” cases.

The bad news is that the devastation to people’s livelihoods is just beginning, while rising dissatisfaction at the lack of government relief support is evident throughout the region.

The regional lockdowns fueled a surge in social media usage, particularly among the young, according to market research hub GlobalWebIndex. The growing activism of youth reflects the “Hong Kong effect,” seen in the widespread admiration for the young activists leading the charge against China’s tightening grip.

Emulating tactics seen in the Hong Kong protests, Thai activists are practicing last-minute “flash mob” demonstrations, rapid dispersals and clever use of social media. Adding local flavor, they have resorted to creativity and satirical humor, such as staging Harry Potter-themed demonstrations and displays of protest art, fashion and music.

Whether on the streets or via social media, dissent is growing over social and political fissures exacerbated by COVID-19. Among key issues, critics are targeting worker rights in Indonesia, government and monarchy in Thailand, along with human rights abuses in Cambodia and the Philippines.

The issues are diverse but appear to have a common theme, characterized by Thomas Carrothers and Andrew O’Donohue, authors of a report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, as a new wave of pandemic-induced “democratic erosion” in South and Southeast Asia. They see social polarization, amplified by the pandemic, as “a serious political disease … that can tear democracies apart.”

Equally stark is a warning by the International Monetary Fund of the potentially destabilizing effects of widening inequality. “Specific measures may trigger protests, but rising tensions quickly transform social unrest into a broader critique of government policies,” it said in its April Fiscal Monitor report. “People take to the streets because of long-standing grievances and perceptions of mistreatment. High or rising levels of poverty and inequality, particularly in countries with weak social safety nets, can contribute to unrest.”

In Indonesia, public indignation over lockdown deprivations and lack of official assistance erupted in riots over the government’s hamfisted efforts to ease labor regulations and natural resources laws in order to lure investors.

With the highest COVID-19 death toll in Southeast Asia, at more than 358,000 cases and nearly 13,000 deaths, the country’s 270 million people are facing their first recession since the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, with the World Bank forecasting a contraction of 2%. Protesters accuse the government of President Joko Widodo of putting the economy ahead of public health concerns. Adding to fierce criticism by the country’s largest trade unions of the proposed changes in labor law, one of the biggest Islamic organizations said the changes would benefit “only capitalists, investors and conglomerates,” and “trample” on ordinary people.

The Philippines is one of Southeast Asia’s coronavirus hotspots — and has also committed one of its least generous stimulus packages. © AP

In the Philippines, also facing its first recession in decades due to COVID-19, criticism has focused on a sharp rise in poverty due to lockdowns and draconian measures, including “shoot to kill” orders issued by President Rodrigo Duterte to enforce quarantine measures. Efforts to quell growing unrest recently saw the violent dispersal of protesters in Manila who were demanding government relief support. A new emergency stimulus package of $3.4 billion ranks at the low end of government relief efforts in Asia, and has failed to stem complaints. According to polling organization Social Weather Stations, the incidence of involuntary hunger has doubled to 16.7% since December and unemployment is soaring. Despite harsh containment measures, the Philippines is just behind Indonesia in COVID-19 cases, with 345,000 as of mid-October, although its 106 million population is less than half the size.

In Malaysia, government and opposition leaders have been fighting for power as public criticism has focused on lax public health management, particularly during recent state elections in Sabah. The government has also cracked down on the media, including arrests and raids on organizations for reporting on harsh treatment of migrant workers.

“As the country navigates a political crisis and a pandemic-stricken economy, young people in Malaysia have become increasingly impatient and frustrated with the state of their country’s leadership,” noted commentator Crystal Teoh writing for The Diplomat. “Although Malaysia has yet to see a youth-led movement as large and widespread as … in neighboring Thailand, it bears careful observation as Malaysia moves in the direction of a possible snap election” in the near future, she said.

In Myanmar, critics among the country’s 22 million social media users are protesting the impact of renewed lockdowns on the poor ahead of Nov. 8 elections. As campaigning has moved online, Facebook accounts have shown “an increase in hate speech and disinformation about parties and candidates,” warned the U.S.-based Carter Center, which is monitoring the poll. The prospect of a deeply flawed election, according to author and historian Thant Myint-U, “won’t help Myanmar address any of its big challenges: violent conflict, climate change, inequality and underdevelopment.”

A resident of a semi-locked down alley looks on in Mandalay, Myanmar. © AP

In Cambodia, which has recorded barely 300 cases of COVID-19 and no deaths among its 16.25 million population, international human rights groups have accused the government of using the pandemic as a pretext to intensify repression of human rights and environmental activists. The government arrested more than 30 Cambodians from January to April for allegedly posting fake news and has jailed 19 activists and artists since July. Human rights groups said the moves were an attempt to curb dissent over the administration’s handling of the pandemic and its economic impact. Sweeping new cybercrime laws have dampened but failed to silence growing complaints on social media.

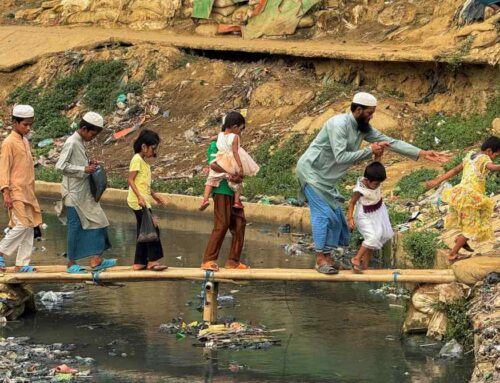

In much of Southeast Asia, the protests have been dominated by the middle class, whether young or old. The irony is that the region’s most vulnerable people — slum dwellers, migrant workers, the rural poor and sex workers — remain voiceless. “You are not really seeing the extreme poor speaking out on social media or on podiums at protests,” said a Southeast Asian diplomat. “With a few exceptions, much of the dissent is ideological. … [I]t’s about freedoms, politics, censorship, you can see it on social media. In cases like Thailand, the people protesting are largely those who can afford to protest; but sooner or later economic hardships will become a key issue, on the podium and on the streets.”

Degrees of debt

The deepest dilemma for many under-resourced governments in Asia lies in growing pressure for stimulus spending to shore up the economy and help the most vulnerable sectors. The average spend by Asian governments on pandemic-related welfare programs has barely reached about 1% of GDP — against Europe’s 16%-plus.

In Southeast Asia, with its threadbare social safety nets, the biggest question is about raising debt levels and increasing budget deficits. In Thailand, where emergency stimulus spending equals nearly 15% of GDP, government debt has risen from 41% to 57% of GDP. Indonesia has also seen its government debt rise from 30% to 37% of GDP.

The region’s governments have taken a mixed approach to emergency relief. Some, such as Cambodia and Myanmar, have offered little, while Malaysia and Thailand have earned wide praise for their efforts. Overall, the East Asia region spends a tiny amount on social protection measures compared to many others, highlighting what the World Bank’s chief economist for East Asia and the Pacific, Aaditya Mattoo, sees as a gaping shortfall, even post-pandemic.

“We are reminded yet again that the rich can telecommute, the poor cannot; the rich can self-isolate, the poor live in slums; children of the rich can do online classes, the poor cannot; the rich have savings, the poor do not,” he said.

Even with increased relief spending, World Bank figures showed that by August, government assistance across the East Asia and Pacific region had reached less than one-quarter of households whose incomes fell and only 10% to 20% of companies that requested assistance since the pandemic began.

In its latest economic report on East Asia and the Pacific region, issued in early October, the World Bank forecast that 38 million more people in the region will fall below the poverty line this year as a result of COVID-19 including 33 million who would otherwise have escaped poverty and 5 million who will fall back below the line. Some economists believe the figure could be more than double that. But even the lower estimate swells the ranks of those living on less than $5.50 per day to 517 million — a reversal of the steady improvement in recent decades.

The numerous victims also include those suffering from what the World Bank calls the “third shock” after the pandemic itself and the resulting global trade slowdown. At the frontline of that shock are the young, particularly women. In Southeast Asia, they are bearing the brunt of the harsh impact on Asia’s job market, according to the International Labor Organization. Nearly 85% of youth employment in the Asia-Pacific is provided by the informal economy, the sector most exposed to the pandemic-related downturn, according to the ILO. As regional labor markets dry up, “the catalyst for change will likely begin with Southeast Asia’s disenfranchised youth — younger populations that are now unemployed and tired of the region’s endemically ineffective governance,” writes Daniel P. Grant, a Southeast Asia specialist, in The Diplomat.

Regardless of age, there is also a new, barely visible category of vulnerable people, mainly in the lower middle-class. They belong to what could be termed the “new COVID poor,” said Mattoo. “They are not part of the usual poverty registry, they are not captured,” he said. They include small and midsize enterprise owners as well as midlevel managers, the self-employed and tens of millions of people who rely on the informal economy.

“Essentially, across the spectrum, people are getting poorer. … All the while, new inequalities are emerging as old ones are being sharpened as a result of COVID-19 and containment measures,” he added.

Across the region, decades of hard-earned economic development gains have been wiped out – in some cases turning the clock back to the days of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. Even in countries providing pandemic-related assistance, many of these “new poor” will not qualify for social welfare handouts or emergency schemes. While Southeast Asia’s middle class was one of the signature success stories of the global economy in the 21st century, their lifestyle is now threatened by rising debts. Some may have to sell a house or car, close a company, pay off employees, move their children from private schools to state education or other measures.

Their problems are reflected in the sharp drop in household incomes since the pandemic began, averaging 50% to 60% across the region, and surging household debt, which in Thailand alone is now approaching 90% of GDP, from 80% in March. Even in Vietnam, among the few Asian countries expected to grow this year, a wave of bankruptcies prompted the recent headline: “With new COVID-19 battle, Vietnam’s middle-class dream deferred.”

In a stark example of the problems facing small businesses, a survey by a group of Thailand-based tourism and hospitality companies in May found that its 85-plus members had retained only 2% of staff on full salaries, with 67% on negotiated reduced salaries, 17% furloughed and 14% laid off. Many cited the urgent need for financial assistance, and said special soft loans from commercial banks were “difficult to impossible to access.”

More than two dozen interviews by Nikkei Asia with mid-level managers and small business owners across Southeast Asia found that those still employed had to accept forced pay cuts, with no reduction in working hours, while the self-employed and business owners feared potentially permanent closures.

Ty Champa, a manager at a boutique hotel in the Cambodian tourist town of Siem Reap, said she had been suspended from work since April, leaving her with no means to support her extended family. “I’ve never experienced something like this in my career. Everything’s going downhill. I don’t know how long I can last with this situation, or how to repay my bank loan,” she said.

Saichon Siva-urai, who owns a traditional Thai massage shop in Bangkok’s Sathorn district, said he suspended his entire staff after the government imposed a shutdown of massage parlors, and struggled to meet expenses such as monthly rent of 50,000 baht ($1,603). “I had no cash in hand, so when the business stopped my income dried up,” he said. Although the ban has been lifted, he doubts his business will survive much longer.

An emptied-out Soi Cowboy in Bangkok, a normally lively red-light district. (Photo by Lauren DeCicca)

“You try and you try. We came out of severe lockdown, but business didn’t recover — I had to pay rent and staff. You reach a point where you just give up,” said Somboon Chaiwath, who recently closed his Bangkok restaurant. “The trouble is in rebuilding — I went back to my hometown, I don’t have the resources or heart to go back to Bangkok and try again.”

From 40 million international visitors last year, tourist arrivals to Thailand have plunged to virtually zero this year. The forecast for next year, assuming that borders reopen, barely exceeds 6 million arrivals. Revenues from both domestic and international tourism have also collapsed, from about 2 trillion baht to barely 350 billion this year, as many hotels face closure, indicating that domestic tourists cannot make up the shortfall.

In recent interviews, workers in the informal and formal economy in the region revealed the scope of the “invisible” crisis that has affected migrant workers — many left stranded and jobless amid evaporating promises of compensation. Many said they were unable to access or qualify for social welfare schemes; most had returned to provincial home towns if they could.

Governments are facing “difficult trade-offs,” said the World Bank’s Mattoo, warning that “significant expenditure on relief or a consumption-supporting stimulus may leave an indebted government less equipped to invest in infrastructure and hence growth.” How governments distribute the burden of public debt across individuals and over time — through indirect taxes, income and profit taxes, inflation or financial repression — will matter for economic growth and distribution, and for future generations, Mattoo noted.

More important, as regional leaders are keenly aware, how they deal with a restless population, emboldened by events in Thailand, Hong Kong and elsewhere, reeling from economic hardships and increasingly critical of their governments, will determine the future — not just of economic recovery but of regional stability and social cohesion. In the absence of fresh ideas, unintentionally prescient advice for those leaders could well lie in the words of embattled Thai Prime Minister Prayuth, who said in an August address: “The future belongs to the young. Let the young lead the way …”

Additional reporting by Nikkei Asia staff writers Yuichi Nitta in Yangon and Erwida Maulia in Jakarta.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW