Myanmar tests Indonesia’s resolve as ASEAN fissures deepen

Bloc’s 2023 chair works quietly to overcome two years of Five Point Consensus failure{1st Photo Caption: ASEAN leaders including Myanmar’s top general, Min Aung Hlaing, agreed in April 2021 on five steps toward resolving the crisis in the war-torn member state. Only one has been accomplished, and the bloc’s unity and credibility are on the line. © Nikkei montage/Source photo by Reuters}

Asia Insight

Myanmar tests Indonesia’s resolve as ASEAN fissures deepen

Bloc’s 2023 chair works quietly to overcome two years of Five Point Consensus failure

GWEN ROBINSON, Nikkei Asia editor-at-large

April 18, 2023 06:00 JST

Updated on April 19, 2023 17:10 JST

PHNOM PENH — Two years after they gathered in Jakarta to forge a consensus on the Myanmar crisis, Association of Southeast Asian Nations leaders have rarely faced such disunity as they prepare for an uneasy summit in Indonesia from May 6 to 11.

In what one regional diplomat described as a “tail wagging the dog” dynamic, the spiraling violence in Myanmar under a savage military regime and determined resistance forces has opened diplomatic and political fault lines while undermining the 10-member group’s international image. Other differences — over attitudes to China and the U.S., or issues such as refugees and human rights — are also threatening ASEAN unity like never before.

“ASEAN is fast being overtaken by events on the ground,” said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, professor of international relations at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. “It either has to regroup and do things differently or fall further into irrelevance and ridicule.”

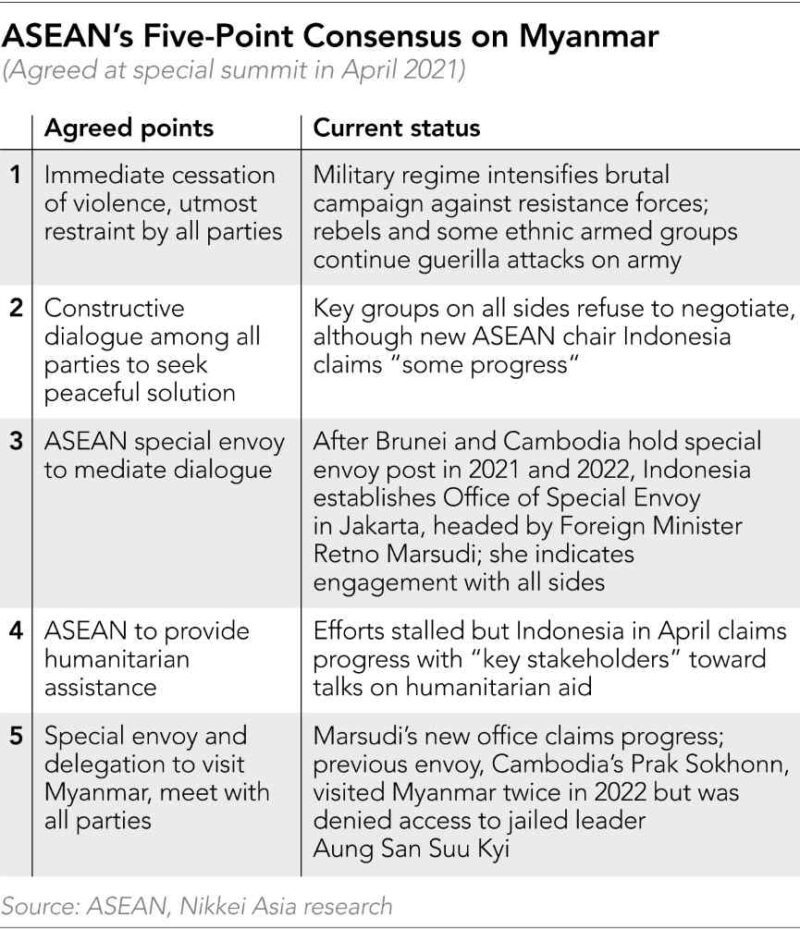

Just two weeks before the anniversary of ASEAN’s increasingly discredited Five Point Consensus on Myanmar, which called for an immediate cessation of violence, a deadly airstrike by regime forces on a pro-democracy gathering in Sagaing state on April 11 offered a brutal reminder of how little has been achieved.

As the ASEAN chair for 2023, Jakarta will be hard-pressed to make progress on its broader agenda, from accelerating negotiations for Timor-Leste’s full membership to signing a treaty to make Southeast Asia a nuclear weapons-free zone. Other priorities include food and energy security, health care, financial stability, economic digitalization and tourism.

Mindful of legacy in the final full year of President Joko Widodo’s administration, Indonesia is eager to achieve a successful grand finale to its chairmanship, with back-to-back events in Jakarta in early September including a high-level ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific forum and the annual East Asia Summit with dialogue partners

On Myanmar, however, Indonesia has signaled determination to make headway while maintaining pressure on Naypyitaw. In the aftermath of the Sagaing attack, it used its prerogative as chair to issue a statement that ASEAN “strongly condemns” the strike.

The world’s preoccupation with Russian aggression in Ukraine and growing fears of a U.S.-China conflict over Taiwan have piled further pressure on Southeast Asia to fix the crisis in its backyard. “Yet ASEAN has been completely impotent,” Thitinan said.

Thitinan traces the recent fractures to well before Myanmar’s military ousted the country’s elected government on Feb. 1, 2021. He pointed to Cambodia’s ASEAN chairmanship in 2012, when a bloc that prided itself on “centrality” and “noninterference” was unable to come up with a joint statement, due to differences over wording on the South China Sea. “As China became more belligerent, Beijing had to undermine ASEAN’s unity to get its way,” he noted. “ASEAN’s internal divide worsened as more crises emerged as a result of U.S.-China tensions. The latest and most existential is the Myanmar coup and civil war.”

Last week’s brazen air attack may have been pivotal. While few governments outside the region have any appetite for hands-on involvement, the global outrage “is an opportunity for the international community to reconsider and shift its approach by no longer deferring to an ineffectual ASEAN,” Thitinan argued. “Global efforts to address ongoing atrocities in Myanmar need to be in collaboration with ASEAN whenever possible but with greater autonomy beyond ASEAN when necessary.”

That is not how Kao Kim Hourn, ASEAN’s new secretary-general, sees it. “You cannot say nothing’s working. Indonesia is very busy engaging in quiet diplomacy. We should be patient a little bit,” he told Nikkei Asia in a recent interview.

But patience is in short supply.

Fighter jets fly during a parade for Myanmar’s 78th Armed Forces Day in Naypyitaw on March 27. (Photo by Ken Kobayashi)

Attitudes toward the bloc are shifting among its 11 key dialogue partners: Australia, China, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, Russia, New Zealand, India, the U.S., Canada and the U.K.

Whether (like China, India and Russia) they favor negotiating with the regime or (like the U.S., EU and U.K.) they condemn military actions and urge ASEAN to pursue an inclusive approach to encompass Myanmar’s parallel National Unity Government, these partners are rethinking how they deal with ASEAN. Privately, diplomats express concern about multilateral matters such as trade, security and the environment.

“If you want something done or discussed in ASEAN you increasingly have to go the bilateral rather than multilateral route,” noted one European diplomat. “You can’t just call the ASEAN secretariat and put a proposal or discuss an issue.”

Still, Indonesia is making quiet efforts to achieve a breakthrough during its chairmanship. It has strengthened the largely ineffectual post of ASEAN special envoy on Myanmar — created as a rotating position shortly after the military takeover — by establishing what it hopes will be a more permanent office for the envoy.

Moe Thuzar, senior fellow and coordinator of the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s Myanmar Studies Programme, said that “in order to maintain a continuity of attention on Myanmar’s ongoing crisis, the special envoy of the ASEAN Chair on Myanmar needs to become the ASEAN Special Envoy on Myanmar, and not tied to the annual chair rotation.”

Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi, pictured on March 31, has strengthened the role of special envoy on Myanmar and says progress has been made.

In a departure from the approach of preceding chairs Brunei and Cambodia, Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi has not taken the envoy post but is heading the office and has built an expert team, featuring veteran Indonesian diplomat Ngurah Swajaya. Marsudi is also spearheading talks that since January have encompassed all sides: Myanmar’s military, ethnic armed groups, the NUG comprised of ousted elected leaders, and civil society, as well as international special envoys including from the United Nations, Europe and Japan. So far, she has not been able to bring rivals to the table, although in a rare April 5 briefing, she said she had met “new stakeholders” who had not been engaged before and that “progress had been made.”

Yohei Sasakawa, Japan’s special envoy on Myanmar, has been particularly influential with Marsudi, urging her to adopt a low-key approach that he likes to call the “Asian way” of diplomacy. He has also urged ASEAN leaders to support the regime’s plans to hold a highly controversial election as the “only exit” from military leadership.

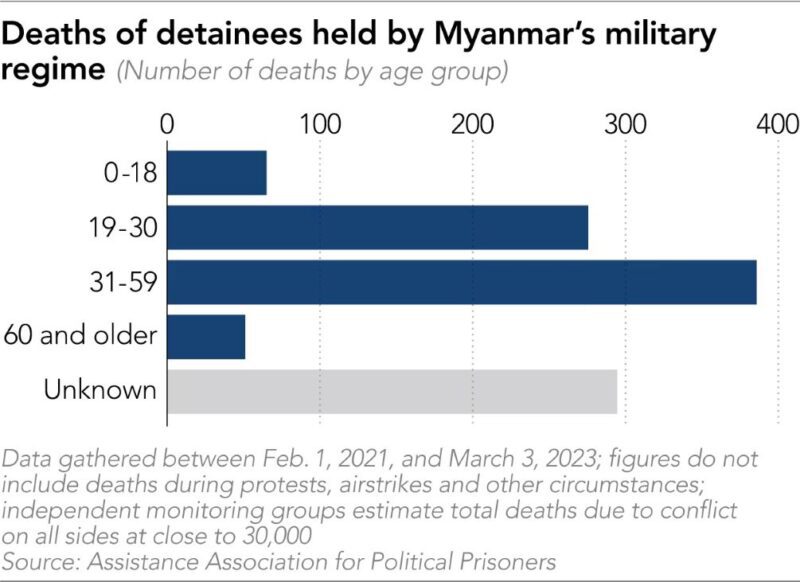

Time is running out. Since the military seized power, nearly 2 million people have been displaced, 21,300 arrested and close to 30,000 killed on all sides, according to independent monitoring groups.

On Monday, the military regime, known as the State Administration Council, announced it had released 3,113 prisoners to mark the traditional new year and “bring joy to the people and address humanitarian concerns.” Activists described this as primarily a publicity stunt ahead of the ASEAN summit, although they acknowledged that it was not yet clear who was freed. A similar move last year saw the SAC release nearly 6,000 prisoners, including some high-profile political detainees.

Either way, there is growing urgency for Indonesia to make tangible progress before the ASEAN chairmanship for 2024 goes to Laos, seen as a virtual cypher for China’s foreign policy priorities in Myanmar.

Marsudi as implementer inherits the Five Point Consensus, broadly agreed between ASEAN leaders and Myanmar’s military chief Min Aung Hlaing in Jakarta in April 2021. Besides halting violence, the plan calls for dialogue; the appointment of a special envoy; humanitarian assistance by ASEAN; and the special envoy’s visit to Myanmar to meet with all sides. The 5PC is also backed by ASEAN’s partners, providing what some critics call a “convenient alibi” for Western governments.

Two years on, the “5PC,” as it is dubbed, borders on farce, with relentless attacks by security forces on civilians and ASEAN aid efforts blocked. State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi remains among countless political prisoners still jailed.

Marsudi maintains the 5PC is the only path. After presenting her 5PC implementation plan to ASEAN foreign ministers in February, she said the consensus is “very important for ASEAN, in particular for the chair, as guidance to address the situation in Myanmar in a united manner.”

Yet, in rarely acknowledged and vaguely worded statements, Min Aung Hlaing himself repudiated the 5PC soon after the April 2021 meeting, insisting he had only agreed to “best efforts.” Indeed, just one point has been implemented so far: the special envoy’s appointment.

Myanmar’s Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the head of the military regime, arrives in Jakarta on April 24, 2021. Although he and other ASEAN leaders settled on the Five Point Consensus, he later claimed to have only agreed to “best efforts.” © (Indonesian Presidential Palace via AP)

Perhaps partly in response to the slow pace and blanket of silence around Jakarta’s diplomatic efforts, some ASEAN members have launched their own “minilateral” initiatives. The resulting dynamic is of a two-track ASEAN, one revolving around the countries of the Mekong region bordering China’s southwest, and the rest. It broadly divides mainland and maritime Southeast Asia.

Thailand emerged as a de facto leader of the “Track 1.5” and convener of the first “non-ASEAN” ASEAN meeting last December, which brought Myanmar representatives together with what Thailand terms ASEAN’s “like-minded” participants.

In a sign of tensions over the unilateral move, Singapore’s foreign minister informed his Thai counterpart in a terse note that Bangkok would be best advised to heed the agreement by ASEAN leaders to exclude Myanmar’s military regime from such events.

Nevertheless, in March, “Track 1.5 roundtable talks” on Myanmar took place in Bangkok’s five-star Anantara hotel, with less than 20 mainly Asian officials, academics and international organizations in attendance. The gathering — co-chaired by Thailand and India — was aimed at “reengaging with Myanmar” and featured both government and private representatives from Myanmar, Thailand’s neighboring Mekong region countries Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, as well as China, Japan, Bangladesh and Indonesia as an observer. International organizations such as the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and Sasakawa’s Nippon Foundation were also represented. U.S. academic Karl Jackson was invited by Thailand to speak about “national reconciliation and the democratic process,” according to officials involved.

It has now been agreed that India will host the next round of the informal talks, as early as next week.

Why was Thailand prepared to risk alienating half of ASEAN?

The impetus came from Thai Foreign Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Don Pramudwinai and his hand-picked special envoy, Pornpimol “Pauline” Kanchanalak. They view the Myanmar crisis as Thailand’s gravest challenge, primarily through an economic prism. Among Bangkok’s main concerns is fear that U.S. sanctions may hit the all-important gas supply to Thailand, by targeting Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE). It is the vital partner for Thailand’s PTTEP behemoth as well as the main foreign exchange earner for Myanmar, bringing at least $1.3 billion in annual revenue.

A Thai soldier sits at a roadblock leading to the Thailand-Myanmar border in December 2021. © Reuters

Myanmar’s parallel NUG has asked PTTEP to suspend dividend payments to MOGE and disclose details of the financial arrangements, and suggested it would take the matter to arbitration in Singapore. U.S. officials have acknowledged MOGE is a potential sanctions target. Some analysts noted the NUG’s move was ill-advised, given the help Thailand has given resistance groups simply by turning a blind eye to the presence of activists.

In a taste of what could come if Bangkok turns on the resistance, Thai authorities in early April handed over three rebel fighters to Myanmar.

The next big issue is the Myanmar military’s plan to hold elections that the NUG, the U.S. and others have decried as a sham. With the likelihood that ASEAN will be divided over the staging of a poll rejected by most of the populace, more dysfunction looms.

“ASEAN cannot move forward at this point without fundamental reforms of the ‘ASEAN Way’ based on consensus and lowest common denominators,” said Thitinan. “One way is to regroup into multi-track modalities around the original five-member core of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand — or ‘ASEAN5+X’ — contingent on issues to be overcome. Waiting for all 10 to agree on critical challenges is less and less of an option.”

On a broader level, ASEAN-minus-Myanmar will continue to hold summits. These set-piece events may even produce grand statements about common geostrategic concerns. But they are quickly becoming symbolic rather than substantive gatherings.

The grouping cannot have it both ways, Thitinan stressed. “ASEAN cannot pretend to put up a united front globally and yet be so divided internally in the face of the Myanmar military’s heinous attacks against the Myanmar people.”

Additional reporting by Francesca Regalado.

Correction: This story has been revised to correct the final day of next month’s ASEAN summit, which is scheduled to run until May 11.

Source Link: NIKKEI ASIAN REVIEW