The Contenders: In Burma, the struggle for power is entering a risky new phase.

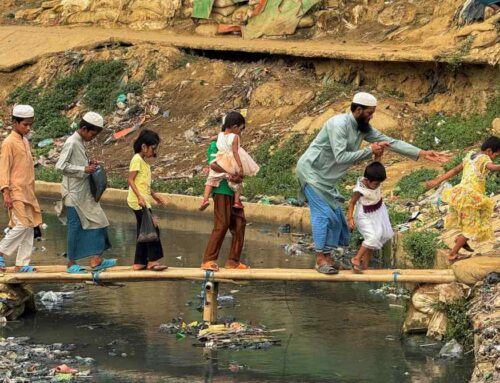

{1st Photo Caption: Thierry Falise/LightRocket via Getty Images}

LAB REPORT

The Contenders

In Burma, the struggle for power is entering a risky new phase.

BY GWEN ROBINSON | JULY 13, 2013, 3:21 AM

A strange thing is happening to Burma’s fledgling democracy. Fueled by the ambitions of a parliamentary powerbroker, a peculiar assortment of political bedfellows — from opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi to ruling party members, ethnic rights activists, and military officers — is posing a growing challenge to executive authority.

For the country’s president, Thein Sein, escalating friction with the legislature is weighing on an ambitious reform program and putting key ministers under unprecedented pressure. Constitutional law experts say the growing tussle between executive and legislative arms highlights Burma’s fiendishly opaque power balance, enshrined in a military-authored constitution, and sets the stage for bigger confrontations ahead.

Much of the new dynamic emanates from the spired halls of the country’s fledgling parliament, inaugurated in early 2011 in Naypyidaw, the shiny new capital 416 miles north of Rangoon. Contrary to earlier predictions that the new parliament would be a toothless “rubber stamp” body, the legislature’s robust grilling of ministers and bureaucrats, its protracted battles to amend draft bills, and its critical stance on some government initiatives have drawn both respect and — increasingly — expressions of concern from some quarters.

Ultimately, some pundits warn, parliamentary actions — including demands to control the government’s conduct of peace negotiations with ethnic rebels — could “neuter” the president and his reformers, or even bring them down. Others play down the impact of the perceived rift, and welcome the display of legislative muscle-flexing as a sign of budding democratic processes.

“It’s healthy. It happens around the world, elected legislatures question and criticize governments — that is democracy in action. And that is what we are seeing in Naypyidaw,” a senior diplomat recently told me.

The problem is that Burma’s parliament is not what any western observer would call a “freely elected body.” In its combined houses, one-quarter of the 664 seats are occupied by active military personnel, chosen by the commander-in-chief and reshuffled on occasion.

Both houses are overwhelmingly dominated by lawmakers from the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), who won their seats in a 2010 election condemned by western governments as deeply flawed. Among a handful of opposition groups is Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), which boycotted the 2010 election but swept 43 of 44 parliamentary seats in by-elections last year. Alongside them are numerous ethnic parties, each with regional priorities and shifting stances on national issues.

The improbable dynamic within this disparate group reached a watershed in late June, the first week of parliament’s current session, when the powerful Lower House attacked the government’s conduct of peace negotiations with ethnic rebels and its awarding of telecoms licenses to foreign companies.

Those events were just the latest signs of escalating tensions that have prompted both foreign and local analysts to warn of a steady parliamentary encroachment on government powers. The trend has gained momentum since last September, when parliament won a showdown over powers of the constitutional court after threatening to impeach the court’s judges and even the president.

In a further blow to executive powers, parliament wrested away authority over appointments to the court. Now, with judicial oversight greatly weakened, critics warn that the legislature in some cases is overplaying its role as a check and balance on executive power.

Given its controversial origins in the much-criticized 2010 election, Burma’s parliament has steadily evolved since its inaugural session in early 2011, which dutifully anointed Thein Sein — the handpicked candidate of outgoing dictator Than Shwe — as president. The pace picked up after Suu Kyi and her neophyte NLD lawmakers entered parliament last April.

Now, elements of the armed forces and the ruling USDP — institutions that formed the backbone of the old military regime and still dominate parliament — are espousing populist lines and backing motions that sometimes run counter to the government they once solidly upheld.

On issues such as foreign investment — crucial to Burma’s reengagement with the West — a surge of protectionist sentiment has seen parliament water down some relatively liberal provisions of investment and commercial laws. More recently, attempts to delay the government’s decision to award two national telecoms licenses to foreign companies suggest clashes ahead over liberalization in that sector.

Yet the so-called conservatives — including military representatives — have taken surprisingly liberal positions on certain political and social issues, for example, on pro-worker labor laws and the release of political prisoners.

Central to an emerging reconfiguration of Burma’s political scene are the declared presidential ambitions of Aung San Suu Kyi and the powerful speaker of parliament’s lower house, Shwe Mann. That became obvious in the opening week of the current parliamentary session in late June, when three events created a sense of crisis within government.

First came an unprecedented attack by Shwe Mann on the government’s peace initiatives with ethnic rebel groups. Claiming that the process had “failed to achieve peace,” he demanded more parliamentary input — in words suggested that U Aung Min, a key member of the president’s team and a former general, had overstepped his authority in talks with rebel groups. It was the first time that the house speaker, a former general who recently took over the ruling party chairmanship from Thein Sein, had openly criticized the government’s approach to peace talks — not to mention a former army colleague.

In another challenge seemingly aimed more directly at Thein Sein, the speaker also called for the convening of the National Defense and Security Council, a military-dominated body, to back parliament’s demand for more involvement in the peace process. The once active council — which includes the president, both house speakers, and the commander-in-chief among its 11 members — meets rarely these days, and mainly over urgent security issues.

The third event came in the form of a direct confrontation over the awarding of two telecoms licenses. Shortly before the government was due to announce the winners, the Lower House backed a motion to postpone the process until it could vote on a long-delayed telecommunications bill. The telecoms contest, Burma’s first major tender to be opened to foreign bidders outside the natural resources sector, had been widely praised by foreign companies for its transparency and efficiency. But some parliamentarians claimed that the local (state-dominated) telecoms industry “risked being monopolized” in the license sell-off. Lawmakers insisted that the government had to heed their call. The government went ahead and announced the license winners anyway.

Shwe Mann’s role in all three events — widely seen as a strike at Thein Sein — drew criticism in unlikely quarters. Some government insiders and lawmakers saw the speaker’s attack on a fellow former general as “personal” and “unjustified.” His call for a security council meeting, some noted, was “excessive” and “too political.”

More significant, the moves have raised broader questions about whether parliament is helping or hindering the government’s reform process — and whether leading lawmakers are pursuing their own personal priorities. Some senior lawmakers dismiss such views. “This perception is just not true,” Hla Myint Oo, a prominent USDP member, said during a legislative break in Naypyidaw. “Parliament has promulgated 53 or so laws since it began; we have shown we can compromise on bills the president does not agree with — and we are working as a check and balance.”

Still, some legal experts note that confrontation between competing power centers is a by-product of Burma’s distinctive “hybrid system” which combines presidential with parliamentary features. “The real test may not be far off,” says Marcus Brand, an international expert on constitutional law, referring to the growing rivalry between parliament and the executive. He notes that the Burmese constitution gives extensive powers to parliament while giving executive powers to the president and his cabinet, making a certain degree of conflict almost inevitable.

Against a backdrop of shifting allegiances and new rivalries, the most striking change has been Aung San Suu Kyi’s rapid metamorphosis from a strident democracy campaigner into a pragmatic politician. Her increasingly close ties with Shwe Mann have generated speculation about a power-sharing deal between the two unlikely allies.

The two hold frequent closed-door meetings on the sidelines of parliament and she has increasingly supported the speaker’s position on a range of issues. Both have declared their presidential ambitions. Both, fueling the over-active rumor mill, have implied they are open to “coalition” arrangements — a prospect that would have been unacceptable to both groups even a year ago.

At a recent lunch in Naypyidaw with other lawmakers, their “special dynamic”, as one aide calls it, was on full view as they sat exchanging remarks and sharing an occasional aside. “Some of us feel uncomfortable with that,” says one senior NLD lawmaker. “But we know the Lady is determined to lead the country; we have to support her, or leave the party. We know Shwe Mann can deliver the military and USDP, and the support needed to amend the constitution.”

According to several Burmese political analysts, there is a “secret deal” between the speaker and opposition leader. The pact, as they see it, would solve Suu Kyi’s need to amend the constitution before the national election in late 2015. She is currently barred from the highest office due to a provision which prohibits Burmese who married or had children with a foreigner from attaining the presidency. Suu Kyi had two children with her late husband, British academic Michael Aris.

Many observers believe it will be impossible to push through such amendments, which require a parliamentary majority of at 75 percent plus the support of at least one military member — what Suu Kyi calls “one brave soldier” — before the poll.

If, as expected, Suu Kyi’s NLD wins a large majority in the election, she will have considerable say in who becomes president, under a system in which parliament (rather than voters) chooses the president. She would back Shwe Mann, and under their so-called “deal,” the two would use their combined powers to effect the necessary constitutional amendment. “Ultimately, he would pass the leadership to her, in a system that enables this to happen,” says a Burmese blogger with close connections to both politicians.

The deal — which some NLD and USDP insiders believe has been agreed — is “politically practicable and foreseeable,” he adds. “But, the point is whether Suu Kyi and Shwe Mann have a viable political strategy for executing it — and whether they can trust each other enough to stick by it.” Indeed, says a local newspaper editor, Suu Kyi would be “idiotic” to strike any deal requiring her voraciously ambitious new ally to hand over power.

The USDP’s secretary-general, Maung Maung Thein, strongly rejects the notion of a deal, saying it would be “impossible.” Tellingly, he doesn’t rule out a potential coalition between Suu Kyi and Shwe Mann’s supporters. But that, he notes, is for a later discussion. “It is too early to mention any coalition, even setting aside the question of whether NLD people would accept the USDP as a partner.”

More realistic, say some, is the possibility of a ‘tandem” solution, one that would move Burma to a French-style system with a president and prime minister — roles that could potentially satisfy both ambitious politicians.

Like everything in Burmese politics, there are potential “spoilers” in either scenario, starting with speculation about the ambitions of military chief, Min Aung Hlaing. Since his promotion earlier this year to the military’s highest rank of senior general, previously held by dictator Than Shwe, his behavior has changed, say diplomats who monitor the military. “He is far more assertive, he is more confident, and he is definitely more political,” says one Asian diplomat.

It’s also possible that Thein Sein, who has gained popularity for his reforms, could try for a second term. After earlier rejecting the prospect, he has recently left the question open. Some advisors say it is primarily to avoid a “lame duck” image in his final phase of presidency; others believe he is considering his prospects.

There is talk of many other scenarios amid the frenzied speculation about the future. This is little wonder, however, considering Burma’s fast but fragile transformation from the days of brutal military rule, when “parliament” was a remote concept and “people’s will” was mentioned only by activists.

That is why recent frictions should be seen in perspective, says Priscilla Clapp, a former United States envoy to Burma. “It is the role of parliaments in democracies to hold the executive branch accountable,” she says. “The recent ‘give-and-take’ between parliament and government in Naypyidaw suggests that democracy is beginning to manifest itself and it is not — as some might suggest — a sign of political crisis or turmoil.”

Clearly Burma’s power structure, once entirely dominated by the generals, increasingly encompasses parliament and government. But the military remains a crucial factor. Even as it watches the erosion of its once-pervasive economic and political privileges, the armed forces still hold the key to the country’s continuing transition.

From the international perspective a revealing development came in late May, when US president Barack Obama welcomed Thein Sein to the White House amid the steadily warming climate of US-Burma relations. Among the more low-profile members of the delegation were two of Burma’s most senior serving generals.

Having exchanged their khaki uniforms for nondescript business suits, the generals quietly became the first active Burmese military officers to enter the Oval Office since Lyndon Johnson received dictator Ne Win in 1966.

As Burma’s ministers of defense and home affairs, Lt. Gen. Wai Lwin and Lt. Gen. Ko Ko occupy two of the military’s three allotted cabinet positions in the quasi-civilian government. Not long ago, their presence in the White House would have been impossible due to sanctions against a regime once condemned by US policymakers as abusive, corrupt, and secretive.

But times have changed, and after their presidential encounter, the generals sallied forth for discreet discussions with their US counterparts in the military and security fields.

Interestingly, the White House earlier rejected Thein Sein’s request to bring along commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing. While the US is increasingly eager to engage Burma, the prospect of seeing its military supremo sitting in the Oval Office was “too much at this early stage of rapprochement,” notes one diplomat.

Nevertheless, Obama’s decision to welcome the two “minister-generals” sent a powerful signal of US acceptance of the Burmese military’s entrenched grip on power. Thein Sein backed that message, telling media in Washington that the military “will always have a special place” in government. Even amid the rise of new players such as parliament and civil society, questions about the military’s future role continue to obsess Burma-watchers.

Not least is the remarkable new accommodation — both within and outside parliament — between Suu Kyi and the military which held her captive for nearly 15 years. Citing her late father, Aung San, independence hero and founder of the modern Burmese army, she told BBC radio early this year that she “loved” the military like a member of her own family. The confession dismayed some supporters while revealing the lengths to which the former political prisoner will go to gain crucial support for her presidential ambitions.

Even for the world’s most famous political prisoner, the challenge is daunting. The 2008 constitution guarantees 25 percent of parliamentary seats to the military, which has signaled its determination to hang on to them. Any return to the barracks will, paradoxically, require military support.

At the same time, however, Burma’s generals are feeling increasing pressure from within the government, and even parliament itself, to curb a critical source of their power: the military’s wide-ranging commercial interests.

For those who want to see the armed forces withdraw to barracks, the most encouraging development has been the steady erosion of its monopolies and dominance of industries ranging from beer and tobacco to auto imports, telecommunications, and construction materials.

Similarly, other military-backed interests such as Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise held an iron grip on the country’s most lucrative exports. A network of active and retired military officers has run these holding companies rather like they ran the country — in secretive and privileged style. Returns went into handsome dividends for the military stakeholders, particularly the top echelons, and into new investments. “Leaders of successive governments used their power to issue licenses and permits to privilege their own business interests and build up a powerful military-economic complex,” says Richard Horsey, a Burma analyst and former UN official in Rangoon.

No longer. As part of Thein Sein’s declared efforts to boost the economy, military-backed companies are no longer exempt from paying tax and must compete against commercial interests for business opportunities. The comfortable old arrangement between bureaucrats and officers is now “in flux,” says Mary Callahan, a Burma expert at the University of Washington.

Over the past six months, for example, Burma military’s once-cozy beer monopoly has been shattered by the government-approved entry of big foreign brands, including Carlsberg, Heineken and ThaiBev, to produce inside the country. More recently, Japan Tobacco and BAT have both won government permission to produce cigarettes in Burma, in a direct challenge to military dominance of the industry.

Meanwhile, the military’s profitable support networks of “crony” businessmen and Chinese companies which have invested more than $14 billion (by official estimates) in Burmese infrastructure and resources projects — much of it through military-controlled firms — have been decimated. The generals have also lost their inside track on lucrative government contracts.

Once accounting for nearly 30 percent of government spending, the military has also lost share of the national budget, from more than 22 percent in 2010 to about 12 percent this year, or possibly 15 per cent with supplementary spending. Over the same period, health and education budgets have nearly trebled, albeit from less than 3 percent in 2010.

More significant, the budget reductions are partly driving the current downsizing of the armed forces, which officially stand at more than 400,000 but in reality barely reach 300,000, according to experts. All these developments are hastening moves by the generals to draw up a new “defense doctrine,” which is said to be based on troop numbers of less than 250,000.

There are compelling reasons for cutting back the regular armed forces. While racial and religious violence — mainly against Muslims including stateless Rohingya — has killed hundreds and destroyed more than 100,000 homes in the past year, conflict with ethnic rebels has quieted after a string of ceasefire agreements. The result is far greater demand for community and riot police than battle-ready soldiers.

Meanwhile, the steady “civilianization” of Burma’s government continues apace, with many mid-level military officials being discreetly moved out of the bureaucracy. Last year alone, more than 700 military officers were transferred from positions in government departments — either back to military units or, more significantly, into the police force. The emergence of Burma’s once-notorious police force, now benefiting from a steady transfer of military personnel and resources, amounts to what Andrew Selth, an expert on the Burmese military, calls the “green-to-blue shift.”

On the ground in Burma’s towns and cities, the new prominence of the police — often clad in crisp, new-looking uniforms — is clearly visible. The new look is a far cry from the poorly equipped and ill-trained units dispatched to quell popular protests. It follows an international outcry over the excessive police crackdown on protestors at a copper mine in western Burma last December. More than 30 were injured amid accusations that police used white phosphorous that severely burned some protestors.

Under a plan adopted in January to expand police units and resources, the police force will increase sharply from its estimated 80,000 personnel. While many see it as a positive development, some human rights groups fear that moves to add or transform units into specialist anti-terrorism units could actually signify either militarization of civilian security operations or the civilianization of military personnel.

Overall, the military-as-institution no longer runs daily life in Burma, says Callahan. Most surprising, perhaps, is the acceptance by commanders of budget pressures and the erosion of their business privileges.

Earlier this year, military chief Min Aung Hlaing made a point of stating that the armed forces will continue to “play a leading role in national politics.” But his tone was almost too defiant, said some experts. “It’s important to see this as a top-down transition, orchestrated and implemented by the political and military elite,” says Horsey. Make no mistake, he adds: “The military remains extremely powerful, and the big political reforms could not have happened without its cooperation — consider how the military bloc in parliament supported reform measures, including in 2011 a decision to release political prisoners.”

But the question remains: Is there a point at which the military will decide that it’s no longer willing to go along?

Short- to mid-term scenarios include a potential military coup or a constitutional crisis and political paralysis. The pessimists argue that the generals are unhappy with humiliating cuts to military budgets and fear that peace agreements with ethnic rebels will render them irrelevant. Some also believe that the “dark forces” behind recent anti-Muslim violence in the country, including activist monks and paramilitaries funded by anti-reform politicians, will exploit the spread of hatred for their own political purposes.

The optimists believe Thein Sein’s reform process has moved the country past the point of no return. Some even predict a victory for pro-democracy forces in 2015 and the introduction of a fully democratic system.

On the economic front, others warn that the country could end up as a larger Cambodia, swamped by tourism, voracious foreign investment, and a “strong-man government.”

Beyond that is a fact that few commentators, both in and outside Burma, seem willing to address: the fragility of Aung San Suu Kyi’s political project. The future of her vast support base as well as her party depends utterly on one woman. She has not — and will not — designate a political heir. With her political pedigree, it would be “impossible” for anyone to succeed her, she once explained to a western diplomat.

Then there is the issue of Burma’s dysfunctional constitutional system and the looming rivalries between executive and legislative branches. Seasoned experts point to the extraordinary protection the military-authored constitution provides the armed forces, arguing that Burma can only become a real democracy through sweeping constitutional reform.

That, of course, would require the once omnipotent military to behave like turkeys voting for Thanksgiving, voluntarily excluding themselves from power. There is barely one expert in the nascent Burma-watching industry who would bet big on that prospect.

But at least there is something to watch — and that, in itself, shows that Burma has come a long way from the dark days of complete isolation and harsh secretive rule. The old elites remain, even as they embark on their own transformation, while the outline of a new ruling configuration slowly takes shape. There can be no question that the once-stagnant country is now on the move — even if its direction remains as unfathomable as the balance of political power.

Gwen Robinson, a former Southeast Asian correspondent for the Financial Times, is a senior fellow at the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

Source Link: FOREIGN POLICY